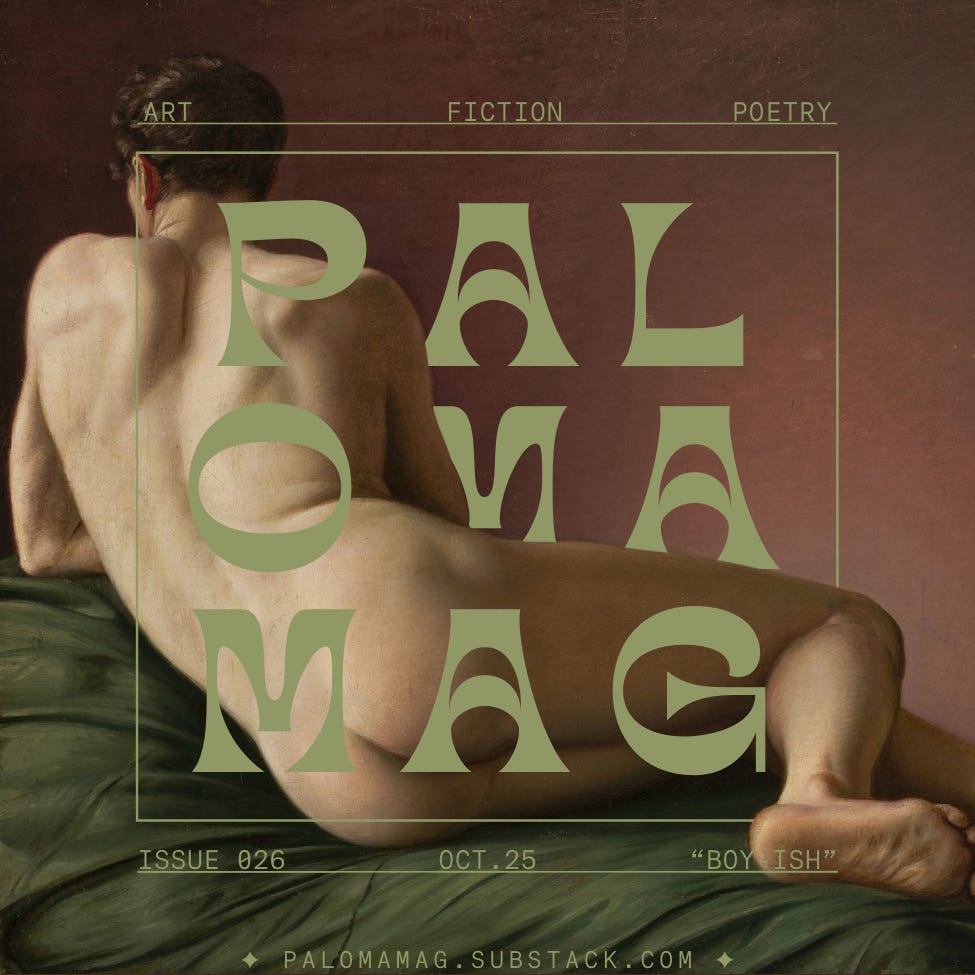

026. BOY-ISH.

how much hinges on what a body can endure?

Welcome to ISSUE 026: BOY-ISH 🫏

Traveling on the unyielding high-speed train, Natalie Diaz’s verses in “Catching Copper” come to my mind: “Yes, my brothers’ bullet / cleans them, makes them / ready for god.” I look out the window at everything Man built. Matter disturbed and rearranged. Scenes of infrastructure and tamed land, with the occasional fallen building. Sitting across from me, the man in the ill-fitting suit closes his sunken eyes.

This month, description and prescription play a forlorn game of tag. What does reclaiming masculinity for oneself look like in a world of its hegemony? When do we repress and when do we perform? And how much exactly hinges on what a body can endure? Whether emotionally distant or invincible, it seems masculinity is a parent we don’t have to love but can never erase the imprint of.

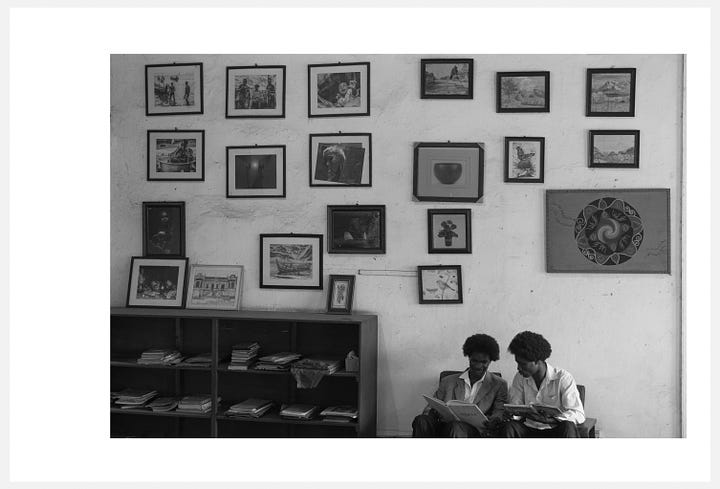

The artists and writers of ISSUE 026 conduct an investigation. thinks about fathers and sons in the fiction piece “Advanced Shit,” echoing ’s photography in “Beyond the Fold” of a recurring duo. Uno Gonzales wakes up “Wondering which of these bruises count” in the poem “bruise butch.” “Priapus on the Prowl,” a fiction piece by Rob Benvie, is “as intimately familiar as a patriarch’s disappointment in his brood.” Meanwhile, Rudi Sandra Burkhardt masterfully loosens and tightens in the delicious poem “The Lasso.” D.G. Devil’s visual art pieces “Testosterone” and “Ain’t Goin’ Back” explore the surreal experience of living as a transgender man in Mississippi. In Ruth J’s thoughtful fiction piece “David,” men are allowed to be boys again, while the photography from the “Beyond Gender” series by Tobias James delights us as a proposal for a new masculine. We close the issue with Libro Levi Bridgeman’s poem “howling,” an ode to the “(so / so thick)” intimacy of the unspoken.

We hope you will be as moved by the poignant vulnerability of this month’s contributors as we are. Welcome to Issue 026!

| poetry editor

Advanced Shit by Philip Traylen [Fiction]

Beyond the Fold by Jibril Naab [Visual Art]

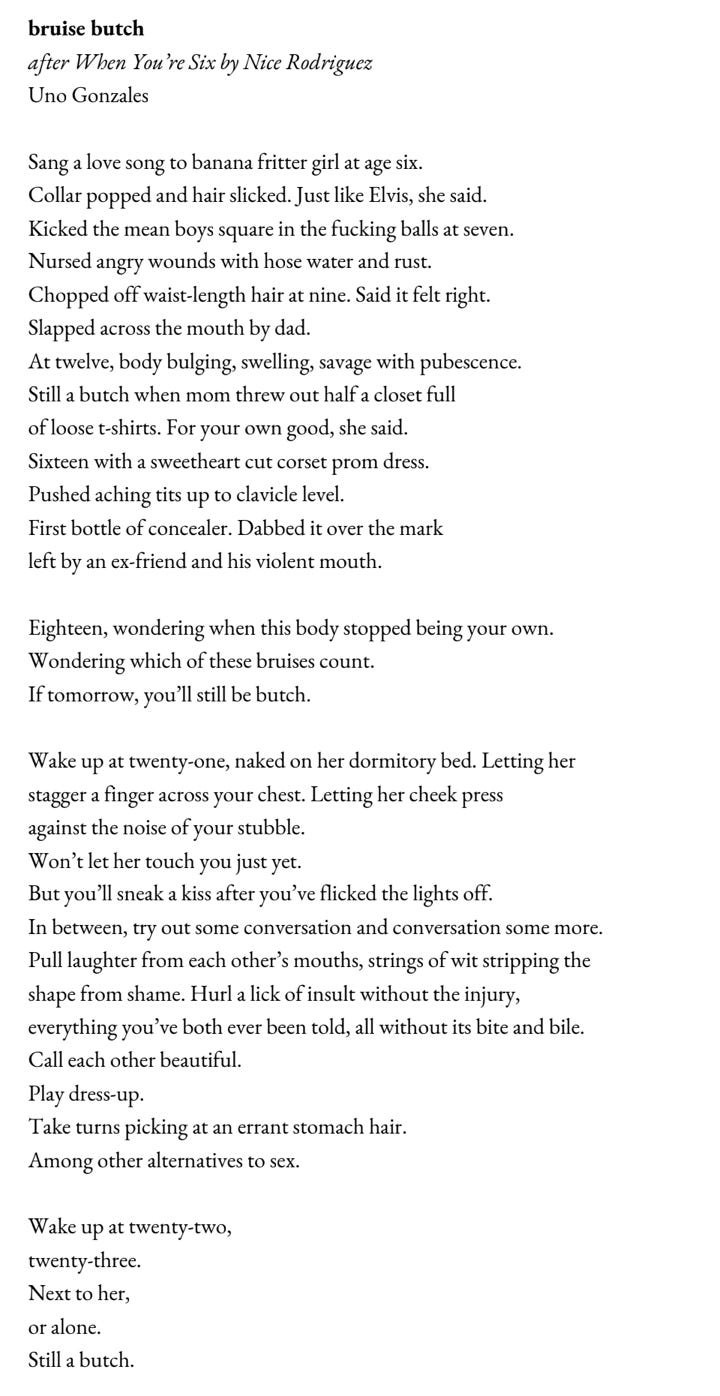

bruise butch by Uno Gonzales [Poetry]

Priapus on the Prowl by Rob Benvie [Fiction]

The Lasso by Rudi Sandra Burkhardt [Poetry]

Testosterone Cypionate and Ain’t Goin’ Back by D.G. Devil [Visual Art]

David by Ruth J. Hiree [Fiction]

From the “Beyond Gender” Series by Tobias James [Visual Art]

howling by Libro Levi Bridgeman [Poetry]

Advanced Shit by Philip Traylen | Substack

The man arrives late, he’s a little tired. He walks in through the door as usual and takes off his coat, puts it over the chair to the north of the table. The boy watches all this, half- heartedly, quite uninterested. He’d put some fish fingers in the oven earlier, they seem to be taking too long; the oven isn’t at its best it seems. It could be to do with winter, some ebb in the voltage, or maybe they’ve made the fish fingers somehow different this time, more resistant to heat. But why would you want to do that? If anything, it would be more advantageous to make fish fingers less resistant to heat, perhaps better still to do nothing at all, to leave things as they are. There’s something counterintuitive about cooking, according to the boy; you don’t have to cook a computer before you use it, you don’t have to cook your friend before you speak to him… But there’s nothing he can do, more and more people around him have started saying things like we’re cooking! or now we’re cooking! and he’ll soon discover something similar going on in various ‘artistic circles:’ everyone is only able (or only willing) to talk about “processes,” as if, unable to “make things,” they’d been reduced to reciting the ingredients of some infinitely long conceptual recipe, which, simply by virtue of existing, has already demonstrated its profound uselessness. What happened to things, he’ll think, some thirty or forty years later, staring at a local lake, thinking lightly of death.

The death he’ll be thinking of will be not so much his as his father’s, who’s just (see above) entered the room and put his coat over the chair (which has a good slope, like a woman’s shoulders). His father’s death, what an interesting thing. It’s so unwieldy, it came so suddenly… But what an uninteresting thing to talk about, there’s so little to say, and, let’s be honest, thinking is just a kind of talking. Fathers die, why think about it, you only need to think about it after it happens — you only can think about it then — and then, why think about it, it’s already happened. Qua boy, he certainly isn’t thinking about it, the idea of his father’s mortality won’t occur to him until he nearly dies himself, in a strange snow-related accident, which won’t happen for another what, twenty, twenty-five years. And during the accident, and even after, he won’t think about his own death at all, only his father’s, which will seem to have been described or promised or perhaps unveiled by the snow, by the strange encircling pain the snow (a mild European avalanche) has visited on him. It will have a fatherly quality as much as a deathly one: nearly dying of it will ‘remind him of his father,’ who always had a sort of snowy quality about him, actually. Some times more than others, and this particular evening (see above) especially so: it’s snowing.

And after placing his shirt on the woman-chair’s shoulders, he brushes himself down a little, to get the snow off, looks over to the boy and says: what are you cooking? You can see for yourself dad, fish. Fish fingers. Advanced shit, the father says. I’m growing up fast, the boy says, I’ll be a man before those fish fingers are ready. Advanced shit, the father says again, modulating his tone to contain the repetition. There’s no need to think about death, neither now nor in the future, neither yours nor anyone else’s, that’s the conclusion the boy will later reach, qua man. All thoughts of death indicate a failure to remember; thoughts of death occur when you either can’t remember or you’ve run out of things to remember, but both of those situations are illusory, he’ll think, at some dumb lake which he came to precisely to think this thought. Advanced shit, he’ll think, remembering it exactly, the tone of voice, the exact scene, which will have effortlessly occurred to him, emerging out of the lake just as the sword does in the story, to be reached out for and gripped hard around the middle. And then, of course, he’ll go back to his own house which he’ll have sort of cobbled together in the meantime, though he’ll have decided, more or less, against having children. Don’t like them much, don’t really see the point, he’ll think, but even that thought will have somewhere in it this strange reductive refrain, which will have become part of him at this point, a part of him that seems central, or perhaps centring. At least a part which it’s easy to take hold of, this little phrase of his dad’s that’s already striking him (see above) in its lightness of touch, its ease, its understanding. This little remark his dad always makes on seeing his son do anything slightly different from what he was doing immediately before. Advanced shit… fathers have said, and, of course, done, much worse, perhaps they’ve even done better, but, he’ll almost certainly think, standing in the shallow water of a local lake, why think about that?

Beyond the Fold by Jibril Naab | Instagram | Substack | Behance

bruise butch by Uno Gonzales | Chill Subs

Priapus on the Prowl by Rob Benvie | The Damagers: A Novel

It’s raining tonight and his penis feels endowed with great power, so he decides to head out early.

This is the sentence with which Zaretsky begins his latest story. It came to him after much consideration of syntax and connotation, understanding as he does how great stories—or at least the ones which find anthologization, earn esteem, fetch prizes, stir envy—often open with an audacious, attention-seizing claim. Stories that demonstrate finesse, authority, mastery. And these are the kinds of stories he desires to write.

■

Here’s what’s supposed to be happening: Priapus, the ithyphallic dreamer, now adrift in our terrestrial realm, is exhibited as a metaphoric representation of virility, in all its assumptions and self-contradictions. Priapus, scion of Dionysus, is archetypally portrayed as wielding an unflagging, abhorrent erection, his engorgement a raging beacon of potency for generations of Lampsacenes and Bithynians, his high-striking foot-long fascinum brandished as a pivot of vitality for Persians and Cairenes. Acts of sexual aggression toward donkeys, also a favoured pastime.

Zaretsky’s story reimagines this myth amid the dreariness of contemporary Toronto. Situating such phallocentric deification in so banal a setting, Zaretsky aims to portray male sexuality in a manner, goes his contention, rarely seen in contemporary fiction: neither as a function of some inherent misogynistic aggression nor as something outright comic, some spoof of feckless men led around by their own wilted dicks. By plundering the symbolism of the ancients, harkening back to antiquity and the clarity of a premodern age, he accesses a near-endless well of allusion, both gratifyingly ironic and stirringly, in a way, beautiful—a pursuit any author sincere in their ambitions, he believes, might reap gainfully in exploring.

But it remains a risky gambit; as François Méliès quipped in Le Sens et La Solitude (1957), “le savant qui habite en allusion comprendre seulement pitances et entre parentheses,” or something like that: Zaretsky, with most of his belongings still cartoned away in a storage space on Dupont, is only able to locate a tertiary reference via Google Books.

He hasn’t really thought about Méliès, or any forms of critical theory at all, since graduate school. He briefly considers calling Melinda to solicit her take—Méliès being an anchoring presence in Melinda’s own thesis, way back when. But engaging Melinda would demand a great deal of energy, something Zaretsky finds in short supply these days; stuffing tortillas at Jack Astor’s four nights a week leaves him depleted beyond cool-headed social activity, his mind too clouded by oily asiago-infused vapours to summon anything close to the full reservoirs of his latent powers.

This life of his, shaped primarily by necessity, is thus one that hardly nurtures nuanced contemplation, critical or otherwise. Still, this is the direction in which his aspirations must be focused. And drunk-dialing his ex, he knows, isn’t something he should get back in the habit of doing.

These, then, are among the challenges he faces.

■

Descriptive passages have never been Zaretsky’s strong suit. Pastiche and germane intertextuality, often by way of apropos epigraphs drawn from opaque sources, are more his thing. In his own reading, he tends to glaze at Steinbeck’s mottled sycamores or Cather’s so-called appearance of permanence. Yet he can concede that a degree of scene-setting is necessary for a story to be convincing. And great writing must, above all else, convince.

So, the task now confronting him is: how to interestingly and, more importantly, sexily describe an unremarkable brasserie in the financial district on a Wednesday evening? How to harness such a thing within a thematic zone of masculine power? Power, after all, is what propels the sexual adventures of restless men, and from where this shapeless thing is to find its form, its fuel, its thrust.

Here goes.

The place is a bit dead tonight, Priapus notes as he shakes rain from his collar and scans the room, which bodes well for opportunities of engagement. The lights are muted, the atmosphere warm. Booths house analysts with loosened ties, pushing their leather-cased Androids around in pilsner spillage. Priapus knows well the ways of such men, young and loud in their tirades and barbs, their high-pitched giggles.

The bar feels snug, but uncozy, like a condom.

Priapus generally keeps his alcohol levels to a minimum, though he’s often inspired by the ecstatic effects distilled beverages produce in others. Timeless humanity, rare grace, can be found in the glowing evening cheeks of those beleaguered by daytime. And relief is clearly needed statim, for a sour mood shrouds Bay Street tonight. A looming government shutdown weighs on equities. The Nikkei 225 has plummeted amid rumours of a trembling fault line and proximate petroleum interests. To boot, the FDIC chairman’s pronouncement of a dire winter has prompted stochastic, resonant ripples.

Tension reigns, a palpable sense of longing. In the parkades, in the subways: a horniness for waste, as intimately familiar as a patriarch’s disappointment in his brood. Priapus moves through the bar with caution. His job is to inflame and nourish, not to peacock. Cycles and patterns, seasons and solstices—these are his parameters, celestially

endowed. Priapus’s love for these mortal fools is his love for the harvest.

Typing this, his love for the harvest, Zaretsky grimaces. He’s fairly certain none of this works. But without any idea of what else to do, where else things might lead, he continues.

■

The Priapus figure suggests bounty, territorial possession—gain, in all respects. Zaretsky himself turned his back on a career in financial services after completing three years of a business degree at York, ennobling himself instead with the mantle of serious fiction writing. But it is his general acquaintance with asset-liability ratios and EBITDA calculations and other industry-specific arcana that now empowers him to develop a winding, complicated passage about Carol, Priapus’s prospective sexual companion/conquest for tonight and, in some respects, the true hero of this story. Carol, signifying some incarnation of what might be considered—though Zaretsky would never put it so starkly—a societal status quo, sits jammed between two analysts in matching pinstripes, their sleeves sliding through an expended plate of wagyu beef carpaccio.

For Priapus, all such ghastliness is just another source of arousal.

When Carol skootches out from her booth and heads for the bar, Priapus swivels on his stool to gleam coyly in her direction. Conversation comes briskly, purposefully; they aren’t children, after all. Carol works in credit ratings, specifically commercial mortgage-backed securities. In her eyes, contact-lensed green, he ascertains a dismal vision of her immediate future: a weeks-long internal audit, late-night teleconferencing with London, alprazolam, a clenched feeling of powerlessness against the immensity of it all.

Onto such arid arroyos, sympathetic tears must surely fall.

Risk analysis, Priapus growls in a highly sexual manner. Full wrap liquidity.

Carol, moving the plot forward, recognizes this cue, and after hastily downing another rye and ginger allows herself to be swept out into the soppy night and a waiting taxi. The rain, as always, is a blessing. In the cab, Priapus fires off a text to himself, a reminder for tomorrow to breathe deeply of Zephyr’s gentleness, to never take such fructifying grace for granted.

Tomorrow, all honour. But tonight, the bounty of the rigid god.

■

A humid evening. Zaretsky types without passion. He calls Melinda.

I’m borny, he says. By which I mean bored and…

Right, I get it. Yes.

Yes?

Yes is also the name of the band he can hear playing on Melinda’s stereo in the background: 1973’s Tales from Topographic Oceans, one of her favourite LPs.

Yes, she says, and what do you need me to do about it?

Zaretsky can’t tell whether this remark expresses contempt or, as he hopes, playfulness. What does he need her to do? A thousand despicable actions come to mind. He bites his tongue.

Will you read my story?

What’s that? You sound strange.

Sorry, he says. I bit my tongue. I was wondering if you’d read this story I’m working on. I feel it’s conceptually strong, but pulling it together is proving a drag.

Melinda seems to not hear him. I’ll have to call you back, she says, I’m just getting into the place now.

Before Zaretsky can ask what place she means exactly, she’s gone.

■

Zaretsky attends the launch for a well-regarded novelist’s latest book. He’d met the writer once previously at another terrible function of this type, a fleeting encounter he’d managed to make both unmemorable and traumatizing, an experience he has little interest in reliving. However, the night will likely be well-attended by the city’s literary crème de la crème, people probably worth knowing—though, of course, he himself harbours nothing but ambivalence concerning such careerist manoeuvres. Such ugliness.

The bar is packed when he arrives, the proceedings already underway. Onstage, the author stands demurely to one side as a representative from her publisher reads from a card, reminding the crowd how she’s earned great admiration not just for her craft but for her longstanding and numerous contributions to the city’s thriving literary culture. To great applause, the author takes the mic and opens with a brief joke that elicits much appreciative laughter—Zaretsky, vying for a bartender’s attention, misses it. The author then begins to read from the book. Like most literary types, she has zero understanding of good microphone technique, and Zaretsky, unable to discern anything said, finds his attentions drifting. He wonders what the author’s vagina might be like. Given her diminutive stature, he imagines it being small and cute, perhaps furtively concealed in thick hair; however, most women these days tend to barber or strip their pubic regions, so that wild bush he imagines is likely tamer. He imagines her lacking any timidity at exposing her vagina, just as she seems undaunted by the attention now gushing her way. A vagina of inspiration, floaty with dreams—genitalia befitting a well-reviewed conjuror of evocative prose. He drinks his beer quickly, enjoying this thought. It makes him more interested in the author and even, possibly, her work, though he still can’t hear a word she says.

Zaretsky briefly entertains the idea of reworking his story-in-progress from the perspective of Priapus’s penis. Or: alternately, the penis and a vagina anticipating it. This idea is a bad one, but an idea nonetheless. If nothing else, Zaretsky has ideas.

Post-reading, attendees mill about the bar. Most, he assumes, are aspiring writers. Detached from the churn, Zaretsky laments all these piteous souls, these dopey-faced hopefuls with their thrift store scarves and tightly carved moustaches.

Just as he considers bolting, Zaretsky sights the author approaching, hand in hand with a woman he believes works for the provincial NDP. Once she’s within earshot, Zaretsky calls to her over the prevailing din, uncertain whether she’ll remember him. She cocks her head in his direction.

Your vagina fires my imagination, Zaretsky says.

The author seems to not hear him, and leans closer. He raises his volume. Is it just as I imagine?

The author looks at him, saying nothing, then continues on her way.

I knew it, Zaretsky thinks.

■

Through the exaltation of Priapus, Zaretsky seeks fanciful turns and frolics, even in the snow-stopped city.

I have soared over wheatfields that pout with peasants’ dreams, Priapus-via-Zaretsky sings. I have poured my viscous weight into bayous born from cockfighters’ nightmares.

This is typed, then deleted, then restored, then cut and pasted aside for later consideration.

François Méliès, the eternally dissatisfied critic whose takedown of the transhistoric metanarrative mode post-Lyotard still haunts many industrious critics of the twenty-first century, committed suicide in the summer of 2002. This was also the season in which Zaretsky, pubescent and pimply, first successfully masturbated to orgasm.

He scrawls a note to himself: convergences?

Despite his many exasperations, Zaretsky often laughs himself awake. In half- consciousness, he writhes with merriment, alone on his futon. But in his waking hours, he is generally a humourless person.

Zaretsky writes, or thinks, or thinks about writing: Prosperity, that sardonic scimitar, suckles us all ex voto suscepto. This phrase is also set aside for later consideration, then almost immediately forgotten.

■

Carol’s loft is described as expansive and odourless; it is, as per Méliès, “a setting that can not be set” (1964). Zaretsky types with glee at detailing the unscuffed hardwood and direct drive turntable, the bar stocked with organic agave extra añejo and expensive frizzante. Priapus and Carol clink champagne flutes like conquerors in repose; the deity’s heart grows as plump with joy as his member does with blood. With fluttering eyelids, Carol states she is a Christian, with fond memories of lively community shamings. Hearing of this, Priapus’s dedication momentarily, almost imperceptibly, wavers.

But then Carol places a disc on the turntable, Yes’s Tales from Topographic Oceans, and Priapus’s harmonic energy, his spiritus, is lifted anew. The creamy synthesizers of Rick Wakeman skim over the intractable toppling of Alan White’s tom-toms. Priapus and Carol revel in the moment, this complex, paralytic bliss.

Zaretsky pauses mid-paragraph. Ramping up the story’s erotic components, shifting from suggestion into the details of actual copulation, will alter its tone considerably. Will Carol suffer any misconstrual when faced with the consequences of what’s about to occur? Can she? Perhaps. But this purest of male bravado, the generosity of this great erection, will persuade her.

Again: the task of the author, as it is the lover’s, is to convince.

In describing Priapus’s penetration of Carol, Zaretsky calls upon memories of his own sexual experiences with Melinda, during their relationship’s enjoyable first seasons: hastily unclothing one another; generously dolloping aloe-based lubricant; then lively, exhausting coition, often on her living room’s plush carpet. Zaretsky is unsure how, precisely, these scenarios deviate, the veracious historical Melinda-driven memory and the reconditioned version featuring Carol. One detail he recalls with confidence: Melinda’s vagina was, and presumably remains, very tight, which often caused his penis’s corona considerable discomfort upon entry. He’d never admitted this to her, however, fearing it would make him appear effete in her eyes.

Side one of Tales, “The Revealing Science of God (Dance of the Dawn),” swirls in a fitting, if not perfectly synchronized, meter with Carol’s gyrations, facilitating her enjoyment of two unabashed, hiccuping orgasms in quick sequence. These climaxes recall battlefields in smoulder; for this, Priapus is, now and always, heavy-hearted. His is a task-oriented melancholy.

Carol is a woman foremost, possessor of the cervix of civilization.

That’s good, Zaretsky thinks as he types. Cervix of civilization. Italicized, for emphasis. He looks the well-regarded local author up on the internet, finding little that’s juicy: a publisher’s bio, a long-neglected photo diary of her travels throughout Eastern Europe, a few reviews of her new book trickling in. This only prompts further speculation concerning her vagina, and vaginas generally—forever elusive, perpetually vexing, and yet, behind high-waisted

Wranglers or a tasteful evening frock, never too far from reach. Though reach is perhaps not the best word.

Zaretsky never, or rarely, masturbates to pornography. He accepts the principle that it pollutes the imagination. But he’s making such great progress on his story that he feels compelled to do something uncharacteristic, even hintingly transgressive. He calls up a video streaming website and unzips with enthusiasm. His motivation, however, quickly wilts. The temptations of these lacquered models only make him feel like a dupe, a patsy to some cynical capitalistic entity. For heroism in this late-modern era thrives in defiance of such ruses, not in being another horny schmoe whacking his wang. Today, true glory is premised on an envisioned future, rather than in triumphs of the past, as it was in, well, the past. The glory of the tax collector, the glory of the personal trainer, the glory of the risk assessor—so on and so forth. Such battles are to be fought in the executive washrooms, in the bated breath anticipating an email attachment, in Holman W. Jenkins Jr.’s opinion columns for the Wall Street Journal.

The true battle is to be fought in inspiration, in that elusive ether of the muse, in bringing to voice the ceaseless clashes of the mythological realm.

The battle is to be fought in the dinner rush, with aching arms laden with dishes like breastplates: the Epic Asiago Chicken Caesar, the Miso Glazed Salmon Bowl, the Ye Olde Faithful Macho Nachos.

The battle is to be fought in tumult, in the markets’ plummets and crests, in those teasing bids and asks.

Waste not these precious days! Priapus/Zaretsky sings/silently swears as he ejaculates inside Carol/onto himself.

■

Zaretsky, plagued by questions, finds his writing stalled. What is being surrendered here, in this story? Priapus’s last links to the foibles of the celestial realm? The demise of any purported reliability? The liquidation of the phallic cult?

If Priapus is a lost icon, what happens next? How does it end?

He fears he might be falling back in love with Melinda. And, more importantly, that any opportunities for his revenge against her for rejecting him are slipping away.

And so, upon receiving an email from her with the subject RE: PRIAPUS ON THE PROWL, his pulse accelerates. The message itself is brief. As promised, she’s read his story’s latest draft, but has refrained from remarking on any specific passages or offering any real depth of critique.

This is all very you, is pretty much all it says.

Zaretsky plugs in his old Epson inkjet printer, unused in over a year, and sends Melinda’s email to be printed. This requires several software updates and a reboot, but finally the machine spits out a printed page. Zaretsky then crumples it, tosses it into his sink, and lights it on fire. The satisfaction he feels in watching the page twist and crumble into ash is meagre, but real.

■

Zaretsky attends another literary event, a night of readings held at an unfashionable microbrewery. Once again he arrives late, and finds the already-thin crowd dwindling. He immediately regrets this whole enterprise. Several of the remaining attendees are gathered in and around a corner booth, engaged in spirited discourse. Some are familiar to him, people in whom he has already invested significant effort toward loathing. He orders a beer and hovers at the bar, waiting to be spoken to.

Then, through the din, he hears his name, or a slurred, clanging version of it. He turns to find the well-regarded author sidling up beside him. Up close, her elfish stature is disarming, as are the revelations her skimpy minidress provides, and as she begins talking he finds it difficult to concentrate on anything she says—a disconnectedness furthered by her being, it is clear, quite drunk.

She leans in, fragrant with chardonnay and Lipsyl.

Why don’t you meet me in the bathroom in, like, seven minutes, she says.

As the author wobbles unsteadily back to the booth and the embrace of her cohort, Zaretsky sips his beer, feeling lousy. This morning he’d discovered a fresh crease on his forehead, a wrinkle, the kind that doesn’t fade with unfurrowing; time is having its brutish way with him. He’s mulled over a wide range of attitudinal leanings he might adopt toward the prospect of getting on in years, but has yet to make up his mind as to which will be most beneficial to his writing career. Cripplingly alcoholic and thrice divorced, François Méliès was sixty-two when he parked his Citröen C3 on the Colorado Street Bridge in Pasadena and leaped to the Arroyo Seco riverbed below; he perished having published nothing of note in almost twenty years. By that benchmark, Zaretsky has the equivalent of one-third of his already-passed life remaining with which to make a mark.

Presumably, a path will make itself clear.

As Zaretsky flees the bar, he finds solace in the hope for such a path. His seething is boundless, galactic, everlasting—and that, at least, is something. His loathing will feed the world, inspiring untold generations to further loathing. This will be his ultimate gift, to history and to myth and to all mankind, nourishing and vast and true, sprung forth from his loins.

The Lasso by Rudi Sandra Burkhardt | Instagram

Testosterone Cypionate by D.G. Devil | Instagram

Ain’t Goin’ Back by D.G. Devil

David by Ruth J. Hiree

The birds looked warped from this high up. Everything in this city did–the buildings and trees were reduced to their colours and shapes. The brightly coloured Camel advertisements and department store sales that David passed on his morning commute lost their detail from where he stood now, looking down.

But the birds–they were eyeless. Their eyes lost that beady look and the individual ruffles in a grounded flock busy puttering in the parks, clogging the sidewalks by congregating around stinking garbage in the sweaty pit of the New York summer, were nothing more than a single rippling mass down below. Up here too, the birds became unfamiliar. It was different up here.

David cinched his rope tight around his waist. This was the slowest part of the day. They were far enough in the build that the boys up top only needed them to tug at the ropes whenever Billie’s bellow echoed down like a trumpet from on high. The day was almost done. The sun would depart in the next hour, and with it the sticky remnants of August heat.

When David arrived on site that morning, the first thing he was told was to watch his mouth around Tony. This was familiar. He usually was paired up with the older man on account of his being the least likely to poke the bear, as Jack affectionately called it. It worked–the two men rarely quarrelled or got nasty. Nothing like the spectacle of Jack and Tony together, who usually devolved into yowling cats, hissing at each other on a hot tin roof.

He felt more than heard Tony’s strained grunt when they heaved the rope at Billie’s call. The two were packed tight together, cornered on the platform. Tony was taller than David, stockier and tanner. Meaner. David craned his neck to see behind Tony’s shoulder. One bird was perched on a beam, looking eyeless. He remembered Georgie sketching birds a lot when they were kids. Those birds would perch on the front gate while Georgie sat on the front step. He would come back inside, brandishing forearms tinged with pink from where the shadow of his head, bent over the copy paper, didn’t reach.

Their mother put one of these up on the refrigerator. David remembered when he came home one afternoon, another August day over a decade ago. Something was lodged in his left shoe the entire walk back from baseball practice–a grey stone, no smaller than a pea. He gave his shoe a good thump on the welcome mat to get it out of the treads. He was pinching the stone between his fingers when he walked through the kitchen in search of a cool drink. He did not know why he held on. He brought his hand up to look at it closely. At that moment, the stone that was raised to his examining eye and the eye of the bird on the page on the fridge ahead of him synced perfectly. A grey stone, a grey eye. David always remembered the pigeon.

This bird, done in childish lines, was the closest to the one that David saw now, sitting on the beams; the queer way its wings refused to sink back into themselves after landing, awkwardly hanging between perching and taking off once more. Disjointed. Shaky.

Billie called out again. Tony huffed again.

On the ground, their eyes were dull yellow. Orange. Sometimes, a gravelly white. Unblinking pearls that tracked absentminded droppings. But with each hundred feet he climbed, they sank to a deeper red. If he looked at them for more than a second, David felt something in his stomach flip. Little devils in the sky, Billie called them.

It wasn’t just the birds that took on a strange air this high. The men here were boys again. Slapping each other’s bare arms and scratched shins, hollering and hooting at whatever and whoever caught their eye. David could hear them now, boisterously rounding off the day’s work. When it was just the two of them, Tony barely spoke. He would say it didn’t bother him at first because he was new and shy. Grateful to not scrape small talk together while standing in the bare bones of a skyscraper. But now, a few months on, David resented the quiet. He would even take the snippy barbs aimed at Jack over the huffed breaths and grunts.

But at least being boys again was comfortable. The skin David had shed and hung up after leaving childhood was waiting for him to take back down and slip back into. Around other boys, David always fell in line. Days in the classroom became rituals of obedience, the smallest boy delighting in not getting shoved around. He enjoyed having a leader to follow. It was much the same with men. Back then, he would crawl into bed and imagine lining up behind the other boys and marching off to sleep. He would stare up at the ceiling fan. Its wooden swirls and loops lulled him into dreams of Montana and horses and cowboys, lissom dreams that came through the door and slunk into his bed, curled into his side and lay there with him. And as the night lapped around him, the small boat of his body carried him through to the dawn bird’s songs, and the cowboy by his side pressed heavy breaths into his neck and rocked him awake until his own breath upon waking was shallow and ashamed.

The call came again. This time, Tony rocked forward, just a little. It was easy falling back into that solitary, seeking version of himself. Perhaps because it never really left him. He was still, decades on, comforted by the sight of someone older, firmer, herding the group as he had been in his school days. The job gave that to him. His first few days there, he was tentative in all things. Rules on how to touch changed all the time. During the hotter days like today, overshirts were shrugged off before their cotton could darken with sweat. Bodies became looser as the day went on. The men swayed close, catching a warm exhale on their napes when they hovered in front of each other, bending and grunting. It was the older men, the ones with strong lines and the broadest shoulders, who set the tone. David started with stuttered movements, unsure of where to grab on and how to let go. Every incidental brush of hands was followed by a pause and blush. This continued until Billie came up behind him one day, slapped his back, and told him to learn how to breathe, kid.

The last call was shouted. Tony began loosening the rope and leaned against a pole. David watched his hands for a second, the deft coiling of fingers. He looked away.

The dreams followed him home. They were the ones you had to be wide awake for, the ones that lend you a blank stare to use on the crowded subway, peaceably allowing you to escape from the thrust of worn bodies at the end of the working day. Silent bodies that still made much noise. Coughing, sighing, singing, yelping, cursing. His damp back itched, his neck an unattractive blotchy mess. The man beside him was heavily doused in perfume, and the woman in front stunk with a heated and heavy smell. Quickly, David’s head, already clouded, began to suffocate in the loud sensations, so different from the hours up on the build, ozonic and pure of little things. Just arms pushing and pulling steadily and the sun beating down steady.

Off the train now. Walk home. More stairs. Bath. Cold food. Bed. Wait to do it all again tomorrow.

He was dreaming again. He knew it. It was the kind of dream that sank into you after a long day, beginning before you had properly fallen asleep. He had expected it. Earlier that evening, he left the bar after one drink. In his apartment, he didn’t have a ceiling fan, so he stared up at the old water stains until his eyes shut.

No cowboys. Just the bar they usually stumbled into after baking in the sun for 12 hours. That, but warped. Outside the dirty window it was daylight, but David had never seen daylight inside the bar. The worn red leather seats were now green and Mick and Teresa, the bartenders who knew the group by name, had their aprons swapped. Tony was there. Miles Davis’ trumpet crooned over the crackly radio. David began to dance.

Every time he spun, pieces of the bar fell away. The chairs and booths, the wooden tables with scratched legs. The poorly framed photographs of sparkling teeth and dark eyes, old patrons long gone. The chipped corners of the hand-painted Open sign. Mick, then Teresa. All that was left was the music. David shut his eyes here too. He was still dancing when he heard laughter.

In the dream, he opened his eyes. Everything else was long gone, but Tony was left. Why would Tony laugh?

The dream rematerialized, but now they were back on the platform, back to work on the same corner as before.

“Davey.”

A bird was on the beam next to David. They both watched Tony come closer. Every step dragged forward, until they could touch, until their hands locked. Breathing. The rules of touch changed again. David pressed his brow against Tony’s shoulder. Tan, stocky. Sweet.

The bird ruffled its feathers and took off, waking David up.

Time for work.

From the “Beyond Gender” Series by Tobias James | Beyond Gender: They Them Us

howling by Libro Levi Bridgeman | Instagram | Website

with thanks to Tink, Mack, Rain, Azara, Mack and Joe

rain asks to meet

we go to

damsel collective

to talk

like bois talk

(thick

with intimacy)

of past loves

that hurt

us

mack asks to meet

we go to

the star

drink hells

talk of

exes

(thick

with intimacy)

old flames

that never

burn

out

tink asks to meet

they come to the house

glug wine

we talk of

fights

(thick

with intimacy)

of wives

that might

nearly

break us

azara asks to meet

joe comes too

and tink

we sit on the patio

under the parasol

rain streaming

smoking

cigarettes

we talk of

deep pain

(thick

with intimacy)

past loves

old flames

wives

but the biggest

feeling

we don’t

speak of

is

the

one

howling

between

us

(so

so thick)Thank you for reading paloma, a monthly art and literature magazine. For information on submitting your work, please see the Submission Guide. You can find us on Instagram, and you can catch up on past issues here.

Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓