Welcome to ISSUE 014: VIVISECTION 🧠

In my dream I was hugely pregnant, my belly distended past my feet, the pain of the thing growing inside me pushing up against the ends of my womb. I was uncomfortable and uneasy. The birthing process was bloody, it was so excruciating it actually woke me up, but I ended up asleep again and labouring for what felt like hours. There were many women holding onto my body, both comforting and cajoling me into finally freeing what I had trapped inside, assuring me I was strong enough to bear this pain, something about women being made for this. What came out of me was not a child, but a lizard. Small and spiny, with little pincers dangling off its front appendages. I didn’t take to my strange lizard child, but instead felt put off, upset that I could create such a thing. Time passed, I healed from the process, but I kept forgetting about my lizard baby and eventually found it dried out under the couch, its tiny body rigid and cold. I was obsessively taking post-natal supplements, shoving handfuls of pills into my mouth and choking them down, but I forgot to nurse the lizard and left it to shrivel up and die alone. I woke up in a cold sweat, my abdomen sore and my pussy aching from being split wide open.

This has been happening to me a lot lately, I wonder if it's the weather changing or if there was some major astrological event. I think this strange phenomenon, waking up in immense pain, means my body is trying to communicate with me. I think it's necessary that I must rid whatever evil, spiny thing that lives inside me.

At the bar with my friends a few nights later, we googled what it could mean. I surveyed followers via an Instagram poll. What was wrong with me that I had so little maternal instinct that I let my child die? Do I hate love? Am I too selfish to give my body over to some form of fetus? I felt an unbearable sense of guilt, I couldn’t stop thinking about the way its pincers looked, like little shells hanging off his tiny arms. I wondered if the lizard was a bad omen, maybe something awful was growing inside me like Cancer or Resentment. Maybe it meant I could never have children. I’ve never wanted them, but that's supposed to be My Choice. Google told us that giving birth to a non-human child could mean many things, so I scrolled through the list until I found a satisfactory reason.

Last week in my seminar class on political economy, we talked about Events. Moments in time and space that have the potential to disrupt the fabric of our society. The professor related political events, like Žižek does, to falling in love, a violent process in which we become a new creature, we may shed our skin or claw at our eyes, desperate to witness a new reality. A reality of love and care. As she spoke, I felt myself getting anxious, my heart started beating weird in my chest as I looked around the room at everyone nodding knowingly, agreeing that love rearranged our inner lives and made a mess of our identities. Everyone seemed to understand the way that love is a gory process of becoming. I realized that maybe I’ve never been in love, I’ve never let myself be ravaged by the chaos of creation in that way. I’ve remained very stoic even in my most romantic endeavors, afraid of shaking things up too much, lest I forget who I am.

I thought about the lizard. I’ve decided it was a message from God. I gave birth to a lizard because I am letting go of my fear and no longer choosing my own suffering. I gave birth to the lizard because I am trying to rid myself of my own sharp pincers, my own tough, spiny protective outer layer. I’m toying with vulnerability. I wanna give birth to something warm and slimy next, I want it to squirm and wail and turn pink when it gets rubbed. I want my womb, and my heart, and my vagina to be open to good things, to be a hospitable place for something to live. Maybe a lover, maybe a child, maybe my own fingers. Whatever it is, I want it to be gory. I want it to disrupt the fabric of my identity, I want to love so hard it becomes an Event.

All of this to say, this month’s contributors were feeling it too, as this issue pushes up against what it means to be vulnerable, spinning out through threads of control, surrender, desire and consequence. “A wound left, greasy and light red,” Katie Haley writes of the ambivalent limbo of pleasure and pain: “feels great in the moment, but sore by morning.”

“I have arrived home to dissect my brain,” writes Camila Islas in the titular “Vivisection,” as her narrator marvels at “how much blood a single head contains.” Later, Emenel Ohsea encounters a vengeful snake and reflects on the discipline of staying still, while Katie Wolf creates archival collages ripe with tension and softness. Finally, essayist Namah returns to analyze the gendered symbolic crisis of style in film, and poet Adil Munim gets trapped in the comfort of a shared song.

Make sure you dig in deep — deep, into the dirt and past the bones — and enjoy.

| co-editor

Patent Leather by Katie Haley [Fiction]

It’s good by Adil Munim [Poetry]

A Song I’d Once Forgotten by Emenel Ohsea [Fiction]

Haptic Fashion in Film by Namah [Culture]

Brace Yourself and A Little Bit of Both by Katie Wolf [Visual Art]

Vivisection by Camila Islas [Fiction]

Patent Leather by Katie Haley | Instagram | Substack

There was patent leather all over me. Feet, chest, and legs caught the overhead light. From a friend’s bed I looked out the window, morning broke and the cottonmouth was so bad every breath felt like sandpaper buffing my throat. I stood quietly, hoping the squeak of my pants, corset, and shoes wouldn’t wake anyone up. Pissed like a hard bullet for what felt like an hour, my crotch hung a little lower than normal. Then I remembered when I came into this same bathroom last night to rub the life out of my clit. When I’m drunk I just want to masturbate, and last night I must’ve gone a little too hard for a little too long. Through the toilet paper I could feel how limp the lips were. When drunk, I’m not precise; jab here, poke there, how ‘bout this spot? I find myself all over again. Which feels great in the moment, but sore by morning. After flushing I looked in the mirror, some glitter crusted on my earlobe that floated down once my fingers brushed it loose. Swollen lips. Some rings that hurt when yanked off. Back in the bedroom bare legs laid atop twisted comforters and mouths breathed loud. Amidst the groggy, I found The Hare, a speed addict and dealer I have shacked up with for the last couple months, two inches deep into a scab on his ankle with tweezers. Because of my arrhythmia I can’t do amphetamines, something my cardiologist reminds me of everytime I see her. Our appointments are more like the D.A.R.E summits of the third grade. Just say no. But despite this I have picked up most of The Hare’s neuroses, my skin is spotted by the same tweezers he uses and I have taken to staying up late emptying bottles of Mod Podge by collaging the walls. He takes one of the patent leather fringes hanging off my top and chews on it while digging in his scab. We sat there for a second, him sucking and plucking, me staring.

“We’ll leave once I get rid of this.” He says, the tweezers now under the film of the scab making a bulge.

Around the room people started to wake up, girls whose feet hadn’t yet forgiven them for the go-go boots, some guys slouched up against the wall with a bong in between them. Me and The Hare are only here because he overdrew his account at the club last night and needed money fast, messaged everyone in his phone if they wanna cop. Max replied with a fat yes and asked us to stick around. I got drunk and The Hare pulled me around by the fringe and drummed his fingers on my sternum. A drunk and a junky in love. You can tell whose stuff is whose back at the apartment: mine is strung randomly, single thongs or socks along the tiles with random t-shirts on the countertops; his is focused in piles, one corner of our bedroom for boxers, another for pants, and so on. It was the same at Max’s, I was rowdy and falling and masturbating on the bath mat while he was in order fluffing every pillow.

Sweat lined The Hare’s brow as he worked on the last strand of scab, tugging it side to side then finally springing it free. A wound left, greasy and light red. He put the flake in his pocket and grabbed my hand to go. The sound of the patent leather filled my ears the whole way home.

It’s good by Adil Munim | Instagram | Website

remember that song you sent me? in a language that neither of us spoke it’s good, you promised i sighed tucked my headphones in, pressed play i listened, and i listened, and i listened until i was timing my steps to the rhythm my feet finding earth to the steady drum, beating breathing until i was floating, caught in the strings of a violin reaching higher towards a dream grounded only by a voice caught between here and somewhere in the rising notes in the melody in the sky itself i evaporated

A Song I’d Once Forgotten by Emenel Ohsea | Instagram

“Where’s the snake in Blake’s poem? Is it in the forest?” I asked dad. He put down the book of children’s verse, all the death and birth in animal fables weighing too heavy. He looked out over the lawn, car parts strewn about for the moment, but to be returned to the garage by the end of that Sunday’s lunch break. A plate of cucumber sandwiches sat on his lap, untouched. He hated them, he always asked for roast beef, but cucumber was what mom fed him. He at least made a show of washing his hands before lunch, which mom expected from him. Otherwise, they’d be black with grease and smearing the pages of the book. “Where’s the snake, dad? Is it in a field?”

“No,” he smiled. “It’s in our yard.” Instantly, he leapt like a panther off the porch and his foot landed hard on the stone path which cut through our grass. A scaly green ribbon had attempted to cross to the other side of the path and my father had been quick to it. The snake was now two withering green swirls, severed by a work boot.

He looked up at me. His eyes were also two green swirls glaring under the brim of his hat. Across the road, the wheat fields rustled in the wind, but he stayed still and looked directly in my eyes. I forgot about the snake dying under him for only a moment.

After what felt like a long period of time, he peeled his killing boot, the left one, off of the pavement with a subtle squelch, mostly swallowed by a singing wind chime on the porch. I was so afraid, that I only looked forward, and did not say a word when he wiped his boots off on the welcome mat, but not before leaving the three bloody boot prints leading up to the porch. I blinked at the red stain. At fourteen years old, it was the reddest red I have ever seen.

Later that night, I went out and picked up the two halves of the snake Daddy sacrificed for some stupid lesson of mine. One half had completed its life’s final mission. I plucked it out the side of the lawn it had been trying to reach right before Daddy crushed it. The other half never made it past where Daddy’s foot landed. Such is the ratio of all living fates, I thought when I reflected on this story much later. I put both halves in an old shoe box I’d been keeping in my room and washed the blood away from the porch after walking to the end of the street to draw water from the well in the dead of night.

I didn’t want to bury the snake in my yard. I felt sorry that my dad might walk over its body again and disturb the snake, making it vengeful. Phantom fangs creeping through the grass and enclosing on my little fingers while I cleaned the pistons of car engines did not appeal to me. So I wrapped the shoebox in a white tablecloth I stole from my mother’s linen closet. If I were caught doing that, I would have gotten the switch to the back three times.

Our house was the only one for four kilometres. No one saw how I brought the snake in my arms down to the end of the intersection my house shared with the neighbouring farmland, carrying the box all respectful. I must have been remembering the way they worked Great Gram’s casket at her funeral. It took six big men from my family, Dad included, to lower her into the earth. I was just six years old at that time.

I don’t think I cried, but I got a deep sense of fear that I was not supposed to be out, and if Mom had woken up and seen me, there would be physical pain to follow.

I walked down the country road in the dark, having strategically left behind any light source; the stars and moon were brilliant that night and the road looked long and unnaturally straight as any road does in the dark’s light.

I eventually walked about four kilometres with this makeshift casket when the tablecloth was starting to unravel unappealingly, so I decided I had gone far enough. There was a public graveyard used by the whole county off to the right. I walked through it until I found a statue of this old guy surrounded by chipmunks, rabbits, squirrels, and birds all running up and down his robe while he held a cross. Some successful Catholic tobacco farmers must have been able to afford it to commemorate a bygone family member. I decided to dig this snake’s grave at the base of the statue so it could be with other animals.

I was tempted to name the snake, like Adam would name all the animals in the garden of Eden. Absolutely not, I’d thought. That would be an insult. The snake didn’t need a name in life, what good would it have done it in death? It was more important that it had dignity.

Doesn’t a name give anything dignity?

Nowadays, I know this to be a stupid human thought which stems from our love of words. Let’s continue. I dug a hole into the ground with a few decorative stones someone had set up at another’s grave.

I picked the casket up which was beginning to look tackier and tackier with its bad wrap job. I buried the box and recited the Blake poem Dad had read to me during our lunch break earlier that day:

“Sleep, sleep, beauty bright, Dreaming in the joys of night; Sleep, sleep; in thy sleep Little sorrows sit and weep. Sweet babe, in thy face Soft desires I can trace, Secret joys and secret smiles, Little pretty infant wiles. As thy softest limbs I feel Smiles as of the morning steal Other thy cheek, and o’er thy breast Where thy little heart doth rest. O the cunning wiles that creep In thy little heart asleep! When thy little heart doth wake, Then the dreadful night shall break.”

When I finished the recitation, I closed my eyes and pretended the poem was a prayer. When I opened my eyes, the air could not leave my lungs and I was on my back. I hadn’t realized right away that I was lying in the hole I had dug. I couldn’t move my head, not left, not right. It was stuck, stargazing, and looking up at the old statue. Its marble birds, and squirrels are deaf to my mental screams. The marble saint above was no help at all. My arms and legs felt gravestone-heavy.

Suddenly, I saw something move along the edge of the grave. A flash of neon green dashing along the grass and earth I’d destroyed. I tried to squint, but my eyelids were unresponsive. I could train my gaze from left to right. I could roll my eyes back and see the wall of dirt loom darker than the sky over my head. I could look down towards my nose, but only stars, statues and the bottom rim of the hole were there. A requiem of crickets, which I had hardly noticed while preparing for the snake funeral, finally cut its chorus. A breeze passed over the rim of the hole and then stopped. I did not get to feel it on my skin.

The night became so quiet that I could hear the blades of grass parting for something huge around the hole. The sound seemed to circle from the top of my head to the bottom of my feet, as though whatever was out there was running laps around me without letting me get a good view of it. If my bladder had been functioning in this state, I would have emptied it in fear.

The head of a snake, much larger than the one my father had killed earlier that day, appeared over the rim of the hole where I had been standing to recite the Blake poem. Its eyes were the colour of coal, and the scales which covered it were each the size of my thumbnail. It was the same snake, I knew it. Somehow, we had changed positions and it had become the size of me and I had become the size of it.

The snake slowly poured itself into my grave and wrapped its tail around my forehead, like a sweatband. It used its strength to lift my head up so I could get a good look at my torso. I was severed in half. Everything from my waist down was at one end of the hole. My torso, neck, and head were at the other end. In the middle, my intestines were steaming in the dirt and soaking the grave soil bloody. I didn’t even try to scream this time.

The snake let my head down gently and crawled across my chest. Its eyes looked into mine and its mouth began to open. For a moment, I thought it was going to swallow me whole. I had heard of snakes doing this to their prey from the books I had read in school, and I was waiting for the jaw to unhinge and begin working from the top of my head down to the base of my abdomen.

Instead, it began to hiss at me.

Ss, ss, th s; Ss, ss; th ss Ss ss s. Ss th ce Ss ss s ce, Ss s ss s, Fff ss. s th ss es s fff Ss s s f th st th, th st th th est. s th s! th th, Th th shh s.

The snake finished its song and then moved away from my view. All that was above me were stars.

When I awoke, I was no longer in the ground, but still in the graveyard. My limbs were not just statuesque, but statue entirely. Before me was the graveyard during the day. Its stones, long forgotten by many relatives, were dull against the morning light. Again, I could only train my gaze up, down, to the left, and to the right, but much like when I was in the grave the night before, I couldn’t move my neck. I could look down and to the left and see my hand frozen in marble and little marble birds and squirrels sat in the ripples of the medieval robe my statue body wore. I could look down and to the right and see the cross I would perpetually hold over the three knots which tied my stony robe together. I could look up and see blue skies dotted with clouds. I thought I should be getting back home to help Dad run the auto shop. My first task each morning was to jack-lift the base of a car so my dad could get underneath it. However, my feet were cairned in place.

Had I become the statue? There was no sound in the graveyard to answer me. A sparrow, a real sparrow, fleshy and full-bodied, landed on the cross I hold. I looked at it. It pecked my hand and I felt nothing, not even loneliness. When the bird took off, leaving sticky green waste dripping down my clenched fist, I felt less alone than I had the night I buried the snake.

The days flew by. I tried counting them, but then forgot to keep track of each time the graveyard light switched from vibrant green to dark. There was rain, and then snow, and then rain. I watched the funerals of family members of people I grew up with, went to school with, and from whom I bought milk and bread at the market. Then, my mother’s funeral happened in a plot not too far away from me. This made me wish I could cry. My father followed soon after. His burial was solemn and lonely, but I was glad I got to see both of my parents put to rest, even if it was while I was trapped in this stoney state.

Occasionally, deer traversed the field. If there was no one paying their respects on the property, they were bold enough to walk up to me, chew the grass where my body lay beneath my feet, and pay reverence to me in a bow. It was after seeing these deer, that I realized I had become the punishment for my father’s killing of the snake; his first and only born, turned to stone. That was the only explanation that I could be at peace with. The deer passed on by. It might have been centuries, but statues haven’t the need for numbers.

One day, two men who walked as though they were husband and wife, something I never seen in my time, visited the cemetery. The one man with ridiculously short trousers stopped before me and looked up at my face.

“I loved St. Francis when I was a boy,” he said, and he and his partner walked on by.

When I was a human, my parents brought me to the United Church, so I did not know the name of the statue I’d attempted to bury the snake beside. Now I knew, but that information had already become useless to me. Over time, I’d begun to think like a statue; not very much at all. My role was only to observe nature.

Many more years must have passed. I watched as the fields on the outer perimeter turned into houses. Houses became towers, and the towers kept getting taller. Then towers were destroyed by wind and fire. The snow no longer came during the months that were supposed to be winter, and the rains got nastier, darker, and heavier, the lightning more frequent and even striking more than twice in one location. The deer had already long stopped visiting me. Then the birds were no longer. Then the humans stopped filling the graveyard and visitors and residents disappeared along with them. The edges of the cross I held were not as sharp as they had been when I first became a statue. One of its branches had snapped right off. The wrinkles of my hands eroded into round, featureless stones, and the marble animals were either knocked off by the elements or became just plain unrecognizable.

The graveyard had turned arid by the sun. Heat and drought extinguished the grass. Some days I was grateful to not have a nervous system.

However, at some point, the rains returned, and the grass did regrow taller than the old groundskeepers had ever once permitted it to. And the birds did sing again. And by the time I eroded into nothing but a stub of stone, a family of deer marched through the thicket around me. They paid my ruined form no more reverence than they had when I was once the statue of St. Francis.

The only animal visitor I did receive came in the form of a giant green snake. Its body parted the grasses and coiled around the base of me, where the ground and my body met. It waited there until a deer came by. I watched it catch and tackle one of the deer in the distance. It unhinged its jaw and swallowed the deer whole. Then, with the deer’s form visible in the outline of the snake, it slithered up to the apex of my body. It crawled on top of me, wrapping round and round. It stared into my eyes, the last remaining detail of the statue that the elements had not totally eroded, and it hissed a song I had long forgotten.

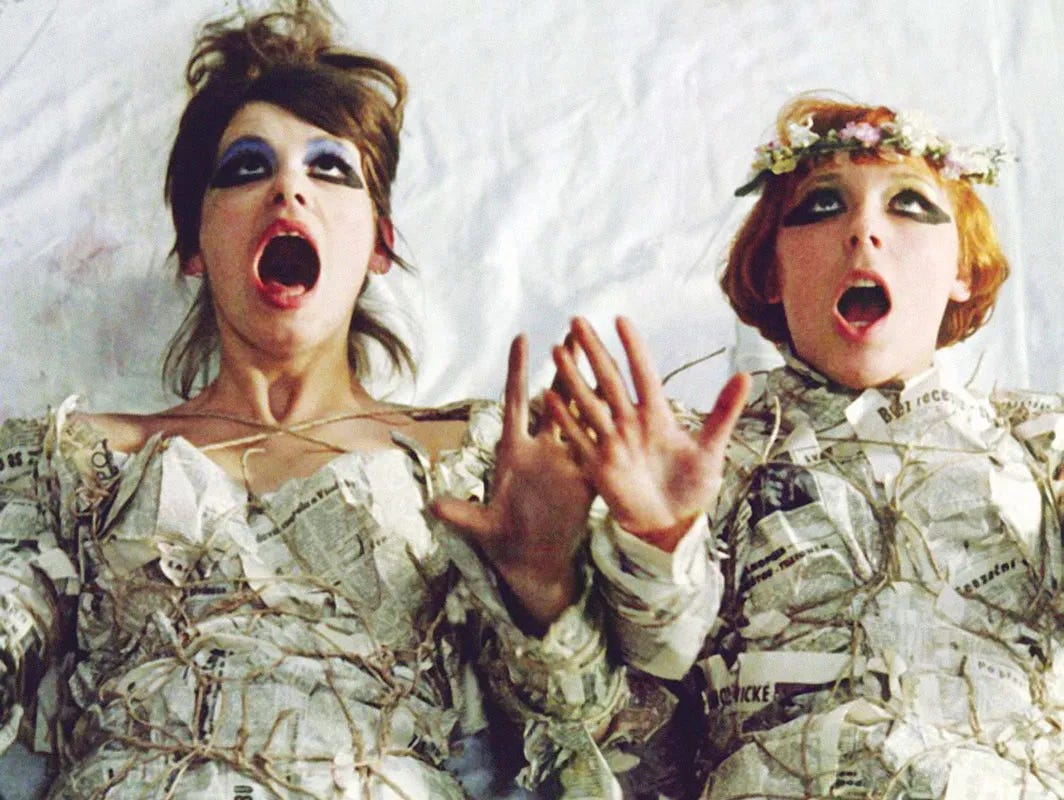

Haptic Fashion in Film by Namah | Substack | Instagram | Letterboxd

Priscilla, Personal Shopper and Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World’s case against representation.

We are in the midst of a Symbolic Crisis. Now, more than ever, femininity is over-coded in meaning. In the age of Girl as both object and consumer, if you aren’t being sold a product, you’re most certainly being sold an idea… and I’ll admit that I like to shop.

Fashion, inevitably, has been caught in this overwrought web of representation, where meaning has been rendered into easily consumable and translatable signs.1 Rituals of beauty have been burdened with yet another layer, where even minimalism risks being over-stylized.

Can I tie my hair up with a bow without invoking soft girl coquette Lana Del Rey fawn bimbo aesthetic? Is the tramp stamp I got, in a desperate attempt to revive my youth, actually just trashy y2k party girl McBling-core? Are my beat-up shoes coded? Are my bare feet? What about the chipped red polish lacquered onto my toenails? Will one misstep cause me to trip and get caught in these threads of meaning until they suffocate me??????????

Luckily, film allows fashion the space to breathe… to transcend these ascribed meanings and return to sensual form, where it is a little more than flesh and skin. The three of these films avoid resorting to the veneer of the self to be understood, and so I am nakedly struck by their beauty. They do more than invite me to identify with a figure; they encourage a sensuous, embodied response to the image.

While costuming aims to imply a distance, ‘haptic’ fashion—derived from the term coined by Laura Marks—attempts to bridge this space between viewer, subject and object.2 In rebellion of both time and place, the women of these films beckon us to the here and now.

They invite us to abandon representation—to not just see, but to touch and feel.

Priscilla (2023)

Victim #1 of the ‘she’s just like me fr’ phenomenon.

Coppola does not tiptoe around the fact that Elvis and Priscilla’s relationship was wholly mediated by objects. Priscilla opens with its namesake gliding across a plush, tufted carpeted—a tactile sensation that is reproduced in both subject and viewer.

Coppola’s emphasis on capturing the texture of the lofty home grounds it in a way, encouraging a mimetic mode of relation. Mimesis, according to Laura Marks, “shifts the hierarchical relationship between subject and object, indeed dissolves the dichotomy between the two, such that erstwhile subjects take on the physical, material qualities of objects, while objects take on the perceptive and knowledgeable qualities of subjects.”3

What Coppola wants us to discern from her evocative style is Priscilla’s double-bind; she is as suffocated by the material objects that surround her in Graceland as she is placated by them. Escape is only possible in the rare moments of intimacy she is afforded with her husband, who looms cold and large like a statue. The turning point of the film occurs when he defrosts, and the two do LSD together. In this scene, Priscilla boldly grabs Elvis by his silk chemise and says Your shirt is breathing—she is ascribing to this garment her own sudden bloom.

This dissolution between subject and object, then, becomes a vector through which to express the complex (and predatory) nature of their relationship. When Priscilla first moves to Graceland, Elvis takes her out shopping… but he speaks to the clothes, while she remains mannequin-mute. It is this dynamic Priscilla learns and later subverts.

As an insecure and arrogant Elvis tries to find meaning in his fame, Priscilla’s growing audacity comes alive through her wardrobe—her bouffant gets bigger, her cat eye darker, her crinoline wider, gently taunting her man: can you find it within me?

Shop The Look: Gucci Spring 2020 Ready-To-Wear Straitjacket

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (2023)

Angela needs a fucking break.

The demarcations between today and tomorrow are lost to the endless demands of her job, a production assistant to a company shooting a workplace safety video. No night sky or morning sun appear across the dashboard of Angela’s car, but her sequined t-shirt dress reflects and amplifies the shifting daylight (the dress reads ‘Club Soda’ in puffy gold appliqué and I’m pretty sure it was sold on dollskill in like, 2018).

When passing drivers call Angela a “dumb bitch” for her freewheeling, her dress yells back with her, one brasher than the other.

But in the way that it is armor, it is also a skin.

The haptic feedback it generates becomes a form of “yielding to one’s environment, rather than dominating it”,4 allowing vulnerability and defeat to seep through Angela’s brutal daily grind. When she falls asleep at the wheel, her stillness is betrayed by the dancing flecks of light.

When she stops to meet her lover, the forgiving sequined fabric becomes a confidant to her affair as it is roughed around and stained with fluid.

During her downtime, the sequins cackle as she speaks profanities into her phone. The decision to shoot in black and white heightens this sensation–like the unspoken arousal of fragile little arm hairs.

As the tedium reaches its promised culmination and we find ourselves on set, Jude switches to filming in color. Both Angela and the dress are vivified, which is now revealed to be even more garish than one had initially imagined.

Shop The Look: Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds, 1965

Personal Shopper (2016)

In Personal Shopper, Maureen (played by Kristen Stewart) acts as a ‘medium’ in two contexts. During the day, she is a personal shopper to a supermodel, Kyra, who is impossible to please. At night, a spiritual conduit to her dead brother with whom she is desperate to convene. Her frustration grows as she is caught between the material and immaterial, failing to transmute in either realm.

In contrast to her glamorous client, Maureen sports understated polos and washed denim. The stone butch look, apart from being a crowd pleaser, consolidates her impervious function in a world of luxury.

But as Maureen becomes enamored with a harnessed organza dress during a visit to the Vionnet store, we learn that this is not due to a lack of inclination. Rather, it is because Kyra has forbidden her from trying on any clothing, despite conveniently being the same size.

It is only when she transgresses this boundary and ruffles through Kyra’s closet, letting the thick spandex bands of stolen lingerie dig into even her taut stomach, that she is able to pierce the threshold separating the living and the dead and sense her brother.

I truly believe that a *good* outfit has the power to do just that. It can lead one to a spiritual breakthrough, for “to be in the presence of an auratic object is more like being in physical contact than like facing a representation.”5

Through fashion, I am forced outside myself as I make contact with a realm I had previously deemed imaginary, inaccessible or insipid. It is, above all, a restoration of faith.

Shop The Look: Used Underwear

Brace Yourself by Katie Wolf | Website

A Little Bit of Both by Katie Wolf

Vivisection by Camila Islas | Instagram | Substack

July 3rd, 1874. Twenty to midnight.

Last meal: one in the afternoon, crackers and fig jam.

Hours without sleep: seventy-seven and counting.

I have arrived home to dissect my brain.

I find myself surging with adrenaline and passion no sleep or hunger could halt. I abandoned Mother for supper and have had no sleep for the last three days. Perhaps the insomnia has affected my ability to crave food, or the lack of nutrition is deteriorating my cerebral nerves. I imagine them slowly dying, one by one, not allowing any information to flow back to the brain. I do not wish to have such a weakened body for the operation, but planning has taken over me; I cannot be interrupted while grasping a hold of my mind.

The obsession increased the more I studied the subject. I have not attended any of the promenades Mother or Edith organized for this week. I know they will grow angry sooner or later. Edith will oblige me to be her chaperone for the upcoming outings despite how much she dislikes my behavior whenever a gentleman joins us. Though trustworthy for compiling my preliminary research, Edith has no greater reverence for the subject and has lost all interest. Indeed, I never believed she would entirely comprehend my studies, nor the gravity of what I plan to accomplish, yet she insisted on participating. Likely an instinct driven purely by gossip. Once, late into a May evening, I had slipped some of her father’s brandy into her beverage as an experiment. She admitted to me that she envied my ability to understand scientific literature. I tried to soothe her jealousy by explaining that Father possessed a vast library and an inherent curiosity for the human body, hence my natural proclivity. I told her how I had procured a copy of Gray’s Anatomy as my gift to Father for his upcoming birthday, and that, due to his untimely sudden death, I retained the book which I study rigorously. Drunk as a sailor, Edith sobbed and patted me on the back. I believe she did so because I talked about Father’s death. To this day, I struggle to understand such an extravagant reaction. I attributed it to alcohol in her veins. As of late, her inquiries into my personal affairs have stopped which has allowed me to submerge myself in my studies.

For the past weeks, I have been gathering the necessary materials for the procedure, a difficult task I pride myself on completing. I required medical materials.No doctor or nurse would allow my entrance to Saint Barts unless I were a patient. I did try to synthesize or self-inflict feverish or anemic symptoms—sprinkle white powder to the face, hold a kettle to the forehead, restrict the intake of red meat—but it was of no use. I later devised a plan to enter the asylum near Chatham, performing a hysterical episode on the street. I would make a fine actress, it seems.

I was assessed briefly by Dr. Lowe, whom I now credit as progenitor of the carnal knowledge I possess about the human brain. As a trained psychiatrist with an inclination toward the demented, he saw right through my act as if I were a specter. He at once inquired about my intentions. I told him my wish to enter medical school and study the brain: to do what you do, doctor! The easy soul took pity on me, said it is such a shame women are not allowed to study medicine, such a shame indeed. I liked him, he proved himself to be useful. Dr. Lowe said he did not believe hysteria was an ‘illness of the ladies’ and he offered his help. Convincing him that I planned to train on dead animals found near the abbey, I asked for some surgical tools and basic medical gear. His face lit up like the sky after a storm. He kept me ‘under observation’ for a couple of days and filled in his notes following the “typical progression” of hysterical episodes. Meanwhile, Dr. Lowe taught me what he knew of the human mind with one of the unreclaimed corpses.

He dressed me with a nurse’s gown and guided me towards the morgue, three levels below the surgical rooms and main entrance. We walked the spiral staircase with a sole candle to guide us. I found it somewhat erotic, our descent into a man-made underworld. By the flickering flame in the darkness I could see Dr. Lowe’s eyes batting at me just the way Edith does with her suitors o’ so subtly. I was there for one thing and one thing only, yet I noted that the sexual atmosphere may benefit me; when men feel attraction, they fold to almost anything. A man’s brain was within the bounds.

Dr. Lowe took the saw and opened the nameless man’s scalp without an ounce of doubt. He cut through the headbone controlling the bleeding. And there it was, shining like a quartz under the fluorescent light of the morgue: the blood fresh, the thoughts gone. The deceased’s brain was beautiful–o’ so beautiful, I shed a tear or two. Dr. Lowe laughed at my expense yet in a complicit manner. I told him I had never seen a real brain before, that I had never felt this way before.

“Feeling what?” he asked.

“Complete.”

He turned around and said if only one could feel this way all the time. O’, doctor, if only! Since being able to prick and look at a human brain, I have not been able to sleep. I can only dream about gray matter, the cerebellum, the intricate veins. I can only dream.

After such an experience, my obsession seemed to have an animation realer than curiosity or interest; the need was more alive than ever. Dr. Lowe discharged me the following day, begging me to write back about my solitary studies as soon as I could. I thanked him with a flirtatious peck on the cheek. He could be useful later on. Mother would like him, she would urge me to invite him for supper, you might finally find a man! No matter.

With tools in hand and the readings done, my fiery obsession ablaze, I set to turn my chambers suitable for the procedure. This morning, I cleaned every surface with ethanol. The sterilized smell soothes me. Mother was outraged. Clara must do the cleaning! Is that not why she is here? I offered her a mischievous grin which she mistakenly accepted as submission. How foolish people act when they do not know the inner workings of the mind!

I decided to spend the night walking with Edith and some Mr. Whalton in order to not raise any suspicions about my designs. Tonight, due to the morbid and embarrassing experience of witnessing my acquaintance, Edith, purring with approbation and chastity at the feet of some plain man, the validity of my obsession is entirely vindicated. I have been driven to this moment, this revelation. Edith and Mr. Whalton insisted on discussing the idea of children and Mr. Whalton’s expectations for a wife. After a long ramble where Mr. Whalton explained what the grief of losing a ‘nice lady’ does to men, they shared their ambitions for the future. I could only roll my eyes as I walked behind them at a steady pace. Edith agreed to everything he said, like a properly domesticated animal taking commands. It was utterly disgraceful. She proceeded to illustrate her dreams to Mr. Whalton with such detail: five offspring for whom to care, a loving husband on which to dote, an embroidery set, and the latest hats on the market.

I had not believed Edith to be so feeble until I heard such rubbish. She described wishing no more for herself than the life for which men thought women wished. I grew sick to my stomach. Mr. Whalton explicitly expressed his affection for Edith’s sensibility, her emotional artfulness, her grace. Unlike her, I had never experienced such a rush of feeling until I saw that corpse’s brain. If only. I felt my eyes glimmer with want, my insides growling with need. I have fallen in love with what we, as a species, yet ignore. Knowing the brain is all I need to be sensible. I felt the crackers I ate at noon rise up, bathed in acid, to my throat. A thread of processed fig jam lingered on my teeth.

As soon as Mr. Whalton led us to Edith’s door, I kissed her goodnight and ran home. Mother was fast asleep. Clara left the warm water and cloths in my chamber as requested. Now it is only a matter of precision. Despite my weakened physical state, my mind is at its strongest. I prepare my desk, place the tools in order. I take out the hypodermic syringe and inject my veins with morphine, careful not to overdo it since I must remain sharp. I must be quick.

The scalpel in my hand is steady. Though I feel drowsy, I keep myself in check by pricking my thigh with a needle whenever my head seems to wobble. I write these observations with my left hand in small intervals without looking as I decipher Gray’s. The book is not clear on where to start the incision. I remember Dr. Lowe slid in four fingers above each temple. The circumference of my cut will not be perfect, but I only have myself on which to dissect, take notes, and explore. I must remain sharp.

My hair has tangled with the scalpel. I have to section each lock to cut the circle whole, just like Clara does when Mother instructs for a ‘city up-do.’ I hold the locks with whatever I can find on my desk: bows, combs, pins which make me look like a hairdresser’s nightmare. It makes me laugh. I can feel and hear the skin of my forehead open as easily as spitting the threads of an inseam. Blood starts dripping, staining my nightgown. Minimal on the front. From the positioned mirror, I can see light bleeding on the back as well. I feel a tingling sensation but nothing more. Half-a-smile appears in the mirror.

I clean the area with a cloth as best as I can. With a pair of tweezers, I lift my scalp. It comes off quite easily—I am surprised, I must note—and I proceed to place it on a plate with boiled water. I feel some breeze on the top of my head but nothing more. My head wobbles. I prick. With gauzes, I scrape my headbone and feel goosebumps down to the cervical. I knock on my head. It feels funny. I cannot hear the actual knock through my bone. What a whimsy! I take a sip of wine, cannot allow myself to be dehydrated or lower my sugar. My lips are the color of my blood. Is it wine or blood? My cheeks flush like Edith when she flirts, like Mother when she receives a compliment. I must have done the correct incision, blood loss is negligible. I lean back so I can see my headbone in the mirror. It is much cleaner than I anticipated. I want to touch it with my bare hands. I feel my own head with my fingertips and I chuckle. I take the saw.

When Dr. Lowe began the second cut, he mentioned how carefully one must saw. You mustn't apply too much pressure or you will pierce the brain. He touched the man’s bone in such a tender, almost maternal, fashion. I replicated the gesture on myself. He proceeded to softly place the saw and follow the circumference of the previous incision, piercing in as if in lapses. Carefully, I do the same. I have managed to practice my precision with clementines and a knife. If anything, I will die without feeling a thing. The thought comforts me. I have never been afraid of my death, nor did I react unreasonably upon Father’s passing. Mother could not understand my calmness, my rapid acceptance, my quiet grief. She had outbursts of rage and melancholy which I did not judge though I could not understand. Edith, for that matter, speaks of romance, becomes flustered by gentlemen, and cannot contain her feelings. My inhibited emotionality had sparked my initial interest in the human brain: I wondered why I do not feel or express myself as the women around me. And here I am, mid-dissection.

I apply pressure. The saw is not an easy tool to maneuver, yet I insist. I note the horrible sound each scrape makes, like chains dragged over a cobblestone path. Nevertheless, I continue. Darker blood oozes around the circumference. Slight increase in blood loss, but nothing of concern. My eyes wander around the room, the morphine lulling my system. I prick myself to no avail. I lose control over the saw. I prick myself again but do not wake. In desperation, I bring the saw to the back of my leg and slash where tender muscle resides. I start and gasp for fresh air. The incision is complete.

I take off the bone-cap and lean back. My head is covered with blood, dripping down my forehead, falling past my back. I am a fountain of ichor and knowledge, I bleed as I advance. Bleeding is good. Bleeding is depth. Bleeding is life. Bleeding is red like wine and I want wine. Take a sip, the tongue is asking for it. It tastes like wood, like cherries, like blood. What does blood taste like? Life, alive. I am dipping my finger in the punchbowl that is now my head. I lick. This is the taste of glory.

I allow the blood to pour like rain. A crimson waterfall. Prick. The floor is flooding with my insides, I am spilling out. Prick. Look at how much blood a single head contains. I take as many gauzes as I can and wait for them to absorb the remaining liquid. Such a frail thing, I am. So weak, so ignorant. I can see my brain. My heartbeat pounds in my ears. I must take a glance at my heart while I am here, open, vulnerable to myself and myself only. There it is, the gray matter. O’, the miracle of knowing one’s own mind!

I place my hand over my brain and I chuckle. I am, actually, not weak. I am strong enough to bear children and yet refuse to do so. To attract and evade men as I see fit. I am a marvel. I dig my thumbs in to take myself out, holding myself high above like a crown. Poor Clara, she will have to scrub off this mess. I hold my brain with one hand, it is incredibly light. Like a feather, yet solid as a rock, it is. I am. This is all of me. Somewhere inside resides what makes me unemotional, intelligent, unafraid. My Father is somewhere in there, too, I know it. I am holding myself.

I have to see what lies beneath with my own eyes. I place my brain over the table and pick up the scalpel. Down the corpus callosum, I divide my brain and crack it open like a walnut. Prick prick. Must I stab my leg again? I should control the blood loss as best I can. I do not seem as concentrated as I should be. My notes are stained in red yet they are still readable. Just look how far I have come. Look, Father, look! My brain in front of me, pulsating it seems. It wants me to slide it open. It whispers my name, our name. Is it me as much as I am it? I slice the thinnest sheet of the frontal lobe, placing it carefully over the petri dish Dr. Lowe gifted me. For your experiments. For future knowledge!

I am getting to know myself in my purest, most natural state. Oh lookit! The corpus callosum is already torn into halves. I hold both hemispheres apart, a peach split down center. The vibrancy of its pink hue, the solitude of its power, the mystery of its gears: a brain so gentle I cry and my tears stream with my blood. Let the brainstem and the heart come as one, become woman. Let me observe and think, and feel and bleed!

I perceive movement near the center of each hemisphere. The magnifying glass is within reach but my right arm does not respond. Well, I will make it so! I prick my abdomen, bringing myself back to my senses. With the utmost care, I place both hemispheres together on the table, a mother laying down her child.

I begin examining the right hemisphere. From the trickles of blood, a tent emerges the size of my ring finger’s tip. Candy-cane colored lights flicker from inside, the sweet smell of caramel and corn emanating in the air as the tent rises. A circus erects. A series of miniature wagons surface from the brain’s crevices and station themselves around the tent. I am hypnotized by the smallness, the intricateness of the figures ascending over the gray matter. I witness horses and colorful posters being flagged on the entrance of the tent. Suddenly, a crowd goes mad: the applause and cheers are as loud as if I were myself inside the tent. I laugh uncontrollably while whistles and stomps of some three hundred sets of feet demand the performance begin. O’, how much Father loved attending the summer carnivals. Mother despised them while we enjoyed every act, every lion and fierce trapezist. The crowd settles down and yellow spotlights dance over the roof of the tent. The show is about to begin! I smile at my remembrance of Father: the cotton candy, the rings of fire, the pups in costumes, his emotion at witnessing it all. I sense the rush of more tears accumulating at the corners of my eyes. I prick myself on my left thigh. What a rush! I turn to the left hemisphere. I have lost track of time with sordid memories of a long gone past.

Through the magnifying glass, I see a casket in the midst of emerging tombstones. They all seem like they are rotting or falling apart, no flowers or epitaphs. The granite graves surround a velvet coffin and the odor of death encircles my chambers. It smells like the morgue. I feel at ease. I like the morgue. I enjoy being the only one alive, the one with the scalpel, the one in control. Perhaps I want to play God. Mother used to say to Father, You cannot be God. O’, silly Mother. I await a growl, the flinging open of the casket to reveal a skeleton beneath. But it remains quiet down there, the tombstones aligned, the stench of rot and peace. I take a pair of tweezers and try my best not to tremble. With the precision of a sewing machine, I lift the coffin’s door and peek inside. Limited visibility at first due to a blood surge flooding the insides of the casket. I should prick myself. Maybe it is almost dawn, the sudden air of morning tells me so. Mother can wake at any moment. Clara could have already started her chores. I must close, I should prick.

There is so much tranquility in this hemisphere, I wish to wrap myself in it, a soothing blanket of stillness. In a swift movement, I prick whichever area of my brain lies inside the casket. I get startled, pricking once more and, Lord, I am alive! The sun rises at the same time I do, a new woman, a complete woman. I look at myself in the mirror. I am majestic. My eyes shine scarlet, I smell of plasma and battle. My brain in my hands, the circus and the funeral. I press it to my breasts. How could I place it back when it is far more useful outside, with me, here and bleeding? I soothe it, a child in my arms. I must tell Dr. Lowe I feel now, all the time. I shall never not feel again! I start to hum a tune and smile. My brain must not return. I mustn’t prick myself if I feel so mesmerized, so joyful. Didn’t everyone want me to be a joyful lady?

I can hear the creaks of the door opening on its hinges. I turn slowly yet utterly euphoric. Mother makes a gesture I cannot comprehend. I show her what I hold in my arms. I hold my mind! She is stupefied. I want to tell her how much I have accomplished tonight, how proud I feel. Such a bliss, knowing yourself this profoundly.

“Mother,” I say in a whisper, “I know my mind.”

Thank you for reading paloma, a monthly art and literature magazine. For information on submitting your work, please see the Submission Guide. You can find us on Twitter and Instagram, and you can catch up on past issues here.

Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓

Marks, Laura U. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Duke University Press, 2000. Pp. 164.

Ibid, 164.

Ibid, 141.

Ibid, 140.

Ibid, 140.

my brain is juiced

Patent Leather felt so visceral and uncomfortable. I loved it.