Derived from the Latin palumbus, Paloma means dove. Free and serene, Paloma is airborne, soaring on high; feminine, delicate, agile, moving through the sky with ease and grace.

Paloma is also a spirited grapefruit and tequila cocktail. Sweet, bitter, and bold, Paloma is a swig of liquid courage, a tangy sour shot, enjoyed amongst friends.

As we conceive of it, Paloma Magazine represents a space to be joint to others by creativity and camaraderie—both peaceful and passionate, a symbol of hope and a shot of liquor.

This newsletter gathers inspiration from magazines, zines, journals, and blogs to become a kind of all-encompassing collection of curios. That is to say: whatever you are working on—be it poetry, short fiction, book review, comic strip, graph, interview, essay, or painting—send it our way! We’re interested! So long as your submission can be said to have an “art and literature” quotient, we’ll consider it! Paloma is a space for writers who are looking to showcase their work without themselves having to establish a readership and maintain frequent publications—submissions are always open and our editorial team strives to establish a laidback and quality outlet.

Our first ever call for papers garnered beautiful and well-written pieces from a number of wonderful artists. This issue heralds several of the topics and themes we find enticing and integral to our writing and reading practices here at Paloma; the submissions that follow run the gamut from poetry to short (non)fiction and engage topics of love, devotion, queerness, loneliness, and (the difficulties of) making (writing) art in the present day. What a way to kick us off!

And finally, some helpful instructions:

Salt the rim of your favourite glass.

Pour equal parts tequila, grapefruit juice, and sparkling water over ice.

Mix in a generous squeeze of lime and add simple syrup to sweeten.

Enjoy!

| co-editor

Tenderness and Ephemera by Gannah Elsoul [Poetry]

Exiting the Cultural Criticism Castle by Namah Jaggi [Non-Fiction; Culture]

Summer Reading Recommendations by Abby Lacelle [Culture]

The Robertson Trap; Niche Flesh; and Anamneses by Emenel Ohsea [Poetry]

Why you so obsessed with me? by Raquel Alvarado [Non-Fiction; Culture]

The beautician and the baked vegetables by Vasundhara Singh [Fiction]

Under the Summer Sun by Cait Barlowe [Culture]

The Vows by Andrea Bass [Poetry]

Tenderness by Gannah Elsoul

how poetic tenderness is. exerting a hypnotizing pull on me, an inexhaustible craving to experience more of it. I see it everywhere.

in the act of peeling fruit for a loved one, the crisp orange skin peeling off, flayed open by your nails, a powdery white left exposed, droplets of juice trickling down the curves.

in the soft gaze of a mother upon her child, who stands with faded scabs on both his knees, entwining false fantasies with reality at a playground.

it makes an appearance in the stained foam of coffee cups, the images through a camera shutter, the smile played on a stranger’s lip.

I see it in the gaps between fingers on one palm, just the right distance for another to fit through it, jigsaw pieces seeking refuge in each other.

and it’s there in the crumpled balls of paper discarded on a girl’s bedroom floor: jagged, forsaken, and soaked in vulnerability. words that have been repetitively altered, an unrelenting inadequacy clinging on to them.

Ephemera by Gannah Elsoul

please, please, please I plead.

let me remain unexposed to the world.

tuck me in a hard shell that’ll conceal my soft core, keep my ripeness from growing rigid.

let me lay in the dark forever, my skin revealed to the blanket ridges only.

let me be satisfied by the cotton filling of my bear as a pillow.

let me bottle the rhythm of my mother’s breathing as she lies asleep next to me.

it could be this serene forever, it could feel this easy.

how sweet it would be if permanence was a fixed state.

we could stay wedged in a corner of life, resistant to the sourness of cherries fading overtime,

retaining the tanginess of the ones our dad brought home after work instead.

the wax from my favorite candle will keep cascading,

the flame dancing on top.

the colors resist each other then coalesce together,

an electrifying cast of blue on the fringes of the blaze

until it becomes nothing but a pool of elixir.

the leaves will shed their color

and grow into a new wrinkly skin we crush under our soles.

and the dew drops will float off the sharp blades of grass,

the culprits behind all the childhood scars that mark my palms.

there lives such sorrow,

in always being plagued by the withering of a moment as it’s still occurring.

Exiting the Cultural Criticism Castle by Namah Jaggi |

Or, How to Write in an Age Where Everything Seems Like an Exercise in Redundancy

I talk too much. I know this about myself. I torment my friends endlessly with my sophistry, spare absolutely no details of my day to my lover, ensnare any stranger who acquiesces into my small talk. Really, I am quite intolerable. Words pour from me easy, seemingly unencumbered by the sort of hesitation I ought to have. I have always been this way, cursed from birth with the unrelenting desire to get a word in. But the realm of writing exists separately from the realm of conversation, one where I inhabit all the anxiety and queasiness that I lack in the other, at once enticed and stilted by the permanence it offers. Speech flows from me easy, bubbly and airy, but I must be weighed down by the heft of my words to finally lay them. All of this is to say—I understand the urge to be the loudest voice in the room, yet shudder at the thought of being taped.

Lately, I’ve found my anxieties to be validated in one way or another. What does one say when everything worth saying seems to have been said already? It truly brings me no joy to dig into ‘girl dinner’, but sometimes, the low-hanging fruit is so ripe that it would be silly not to pick it. In girl dinner, we saw the tiresome cycle of discourse play itself out at a sonic rate. An endless set of hungry hands reaching and grappling to grasp this otherwise simple concept, desperate to be the ones to define it, tripping over their loose ends to assert its significance. The takes that this hunger produced ran the gamut—girl dinner is x, girl dinner is y, the fact that people think it’s x actually makes it y, the fact that people think it’s y actually makes it x, and that perhaps the problem lies not in the answers but the question itself. Eventually (very quickly), the discourse surrounding girl dinner detached from the originating phenomena and simply entered into conversation with itself. Some, perhaps, would argue that this generative nature of girl dinner is precisely indicative of its value, and the value of cultural criticism as a whole. But such a stance would be much easier to digest if the tide did not fall as quickly as it rose, struggling to find its way back to land.

My idealism (or naivete, or folly) has convinced me that art, such as writing, deserves to exist outside the tides of industry, serving purposes that are as nebulous as they are important. So, it can be quite disheartening when what you want to write is at odds with the sort of writing that is in demand. I am already laughably late in speaking about girl dinner, vastly missing the one-week window in which I had a shot at saying something that mattered. An obvious part of the equation is that this particular subject matter did not warrant nearly as much consideration as it garnered, but cultural criticism’s obsession with coinage and nippy writing is ever-enduring. While the motivations behind this rampant pathologization are probably mundanely self-interested, its effects can be sinister. There’s a violence inherent to definition that seeks to quiet all other variance, posit itself as an authority and dictate how others must feel. In defining that which is undefinable, discerning that which is indiscernible and sensationalizing the unsensational, we make plain old existence more amenable to commodification (the last stage of the discourse cycle is the snarky twitter of a fast food chain).

In addition to those who are desperate to capture it, the moment itself is responsible for the sorts of skewed incentives we face. Many things are happening—our attention has never been pulled so hard in so many different directions. While this observation is not novel, it is worth repeating. One would think (hope?) that such a raucous demand would elevate our attention to something more precious (as consumers, it is all that we have to give), but this could not be further from the truth.

In defining that which is undefinable, discerning that which is indiscernible and sensationalizing the unsensational, we make plain old existence more amenable to commodification.

It has become increasingly easy to write something which is relevant to the moment but depreciates in value soon after it has passed (and yes, I know that this essay in itself is no less discursive). The Attentional Economy (and its appendages) have trapped us in a didactic yet fleeting parley, where the goal is not to craft a lasting impression but get a word in as loudly and quickly as you can. Writing has been reduced to the level of conversation and in such, it is forced to conform to its conventions. Timing is everything, and everything must be said with the self-effacing knowledge that it will cease to matter as soon as it's uttered. Time functions differently when it isn't tied to space—online, decades happen every week. The best time to be anywhere on the internet was right before you got there. I convince myself I know how its clocks tick, that I know how to stop it dead in its tracks. But I’m late to everything.

Nobody loves to chat more than I do. Yet, I can’t help but feel like it's worth preserving writing’s special status—whether it’s for the sake of quality, the limits of our attention or simply having something to talk about. At the start of every week, I promise myself (and admittedly only somewhat succeed) to turn my consumption into a considered act, to treat it with the sort of regard it deserves. This attitude inevitably extends to what I choose to write about, hoping that it wriggles its way into someone else’s consideration.

For a long time, I hoped to be a cultural diagnostician—prophetic in the way I string the current with the theoretical, quick to make the connections and even quicker to pen them down. As a young girl on the internet with limited access to traditional means of publishing, it is seriously hard not to feel like that is the only way to get people to care about what you have to say. But lately, I find myself writing about beauty and love, womanhood and history, creation and decay—subjects that are so enduring that my labor over them never feels lost. And so, I find myself embedded in a tradition rather than caught in a moment. For the first time, I think hard—pausing and hesitating for as long as I want—for I know that the conversation will be waiting for me when I have something worth saying.

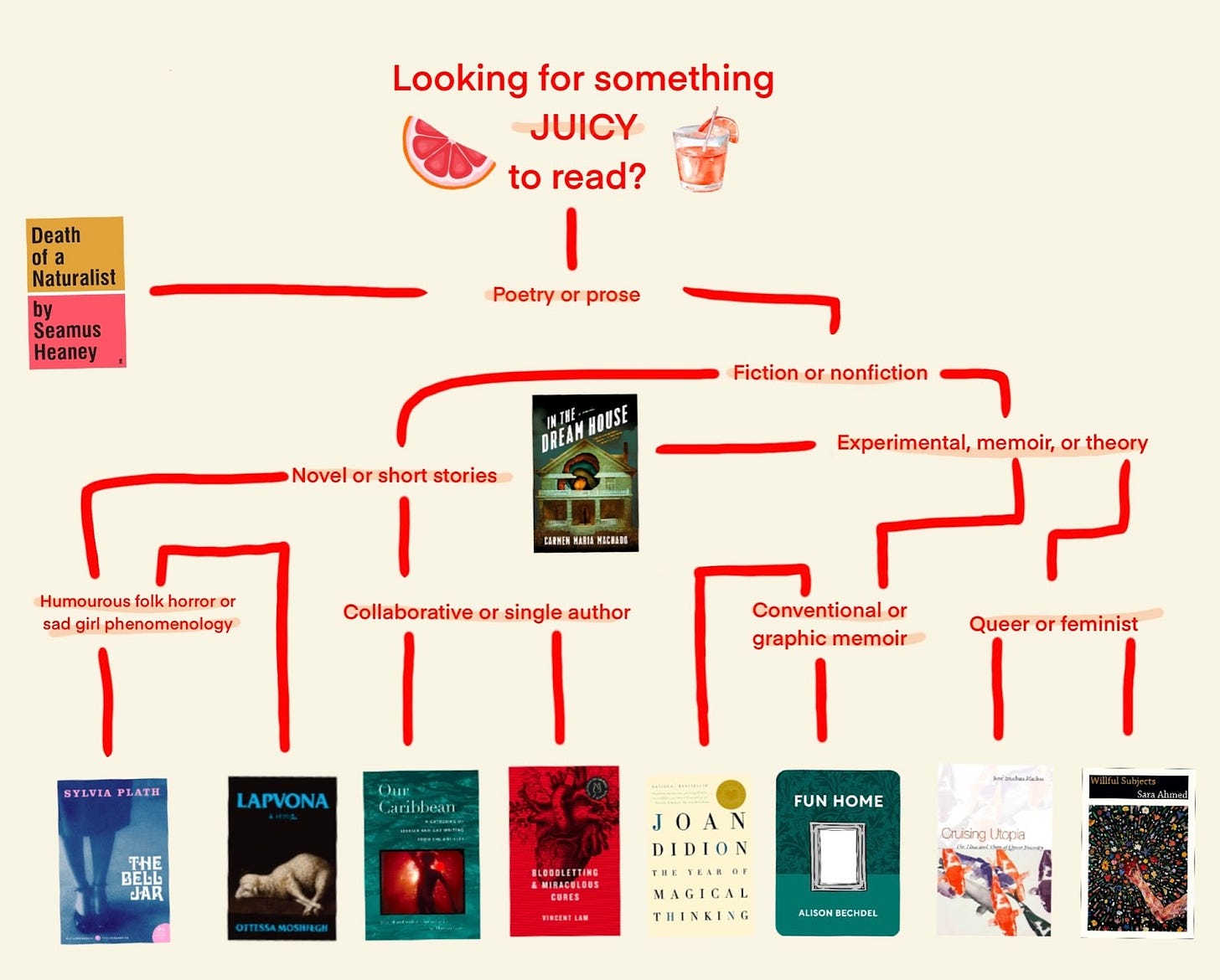

Summer Reading Recommendations by Abby Lacelle

Summer isn’t over yet! If you’re looking to add a couple more great books to your Goodreads before the fall, but you aren’t sure what to pick up next, look no further—this flowchart is designed to help you find just what you want. —

Death of a Naturalist / In the Dream House / The Bell Jar / Lapvona / Our Caribbean: A Gathering of Lesbian and Gay Writing from the Antilles / Bloodletting & Miraculous Cures / The Year of Magical Thinking / Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic / Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity / Willful Subjects

The Robertson Trap by Emenel Ohsea

There was a doctor of dead things fixing wings

to the corpses of crickets.

An entomologist’s toolbox; pins, preservatives, precision, and delicacy.

He worked under lamplight; yellow beams caught every antenna.

He preened the bug for a future audience.

Some words of solution to me as he dipped another wing in glue:

We will have texting,

Skype, and plenty of FaceTime.

I will be back mais rápido

To see you again.

In December, parallel tracks scarred the snow in my driveway.

The doctor flew south, and I migrated indoors.

After twelve months of waiting, I rinsed the snow out of my hair.

Just defrosted a little,

and waxed my wings for the red eye of my webcam.

I became mobile within the frame for him, bumping

against the edges.

I played back the video I made

and saw the short, chirping song of summer;

saw myself as pinned

to a short cork board.

Niche Flesh by Emenel Ohsea

He claims I enmeshed a home inside him.

There I go, being an injured pest again.

Does he know

a nest of ribs cages me,

while I inconvenience his silent heart

with song?

When a robin enters your house,

shoo it before it breaks itself against the pane.

Anamneses by Emenel Ohsea

Google says take left on Strange Street.

Sounds good because Brick Street is closed for construction.

Strange Street is the safer path because the expected could occur,

something unexpected.

Why do I keep turning down Strange Street,

where a taciturn tongue

offers a game of tag?

Why you so obsessed with me? by Raquel Alvarado |

Tracing a genealogy of obsession through Elizabeth Smart’s By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945), Annie Ernaux’s The Possession (2002), and Sheena Patel’s I’m a Fan (2023).

“No, my advocates, my angels with sadist eyes, this is the beginning of my life, or the end.” — Elizabeth Smart

So begins our unnamed protagonist’s descent into love-induced madness in Elizabeth Smart’s 1945 novel-slash-poem, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. But this is no lamentation for the lovelorn Smart, whose narrative stand-in loosely follows a trajectory similar to her own; rather, this is an exaltation of love and a steadfast commitment to endure its consequences.

Canadian-born Smart first came across the poetry of George Barker in the late 1930’s, and after falling in love with his writing, she used various tricks and wiles to bring him and his wife (!) to the United States, at which point she and Barker began a decades-long affair that produced four of his 15 children. After Smart became pregnant in 1941 with her first child, she returned to Canada alone. When Barker tried to visit, he was turned away due to “moral turpitude” and the influence of Smart’s wealthy parents, who likewise lobbied to have By Grand Central Station banned within Canada. They were successful in their suppression for some time–it wasn’t until Smart’s opus was republished in the 1960’s that she finally received recognition for her haunting, jubilant, and exacting work, allowing her to leave her copywriting job and purchase a home and writing space of her own.

It’s all the more remarkable, then, that By Grand Central Station reads as such a lucid, clear-eyed vision of both the present and the future. Smart’s narrator is arrested while engaging in an affair with a married man, and while she is aware that her unwed pregnancy makes her a social pariah, her commitment to love is so great that instead she feels pity for the policemen arresting her, who snicker and sneer: “They are taking me away in a police car. The policeman’s wife sits stiffly in the front seat. They are prosecuting me for silence and for love.”

The rest of the novel takes place in the in-between, as Smart, like her narrator, is separated from Barker while pregnant with his child. Her despondency takes on an epic, biblical proportion, as she waits for their reunion: “Girls in love, be harlots, it hurts less,” she warns. But despite her lucidity, she cannot conceive of their separation as an ending; rather, the novel concludes with a question for her lover, whispered into a vacuous, empty abyss.

“I am writing jealousy as I lived it, tracking and accumulating the desires, sensations, and actions that were mine during this period. It’s the only way for me to make something real of my obsession.” — Annie Ernaux

Unlike By Grand Central Station, Annie Ernaux’s 2002 The Possession starts at the definitive end of a love affair. Published originally in French as L’occupation, The Possession sees obsession as an invasion, an enemy combatant occupying the territory of love. When Ernaux’s narrator–also an unnamed stand-in for the author herself–learns that her ex-lover has a new mistress, her jealousy towards this unknown other woman becomes both an all-consuming occupation, and a ghostly possession.

But the real guts at the heart of an Ernaux novel–the raw, beating thing–is how deftly she navigates both her self-consciousness and her brazen desire to tell us the whole truth: “I have always wanted to write as if I would be gone when the book was published” is followed directly by “The first thing I did after waking up was grab his cock–stiff with sleep–and hold still, as if hanging onto a branch.”

And this is the gift of a doggedly working-class writer like Ernaux, whose Nobel Prize acceptance speech revealed a lifelong commitment to writing in order to “avenge my people.” In her commitment to tracing the sharpest edges of her life, she transcends its mundanity, much like Smart: “It is no longer my desire, my jealousy, in these pages–it is of desire, of jealousy; I am working in invisible things.” The catharsis of both novels is in the willingness of the writers to say, here is my whole heart, left on the page.

“When I pointlessly argue and fight with him, I feel like I am fighting the very structures of the old colonial forces, where he has, holds and takes, and I give, offer and ask for nothing in return.” — Sheena Patel

In the genealogy of female desire and obsession, Smart represents a metered, controlled exaltation of a woman crying out for her lover to return. Ernaux, conversely, marks a confessional turn toward introspection as she revisits her capricious, love-addled state of mind from a distance. Sheena Patel’s 2023 publication of I’m a Fan sets to burn the whole foundation to the fucking ground.

In I’m a Fan (a title that could have worked for By Grand Central Station, mind you), we find no clear structure. It’s the opposite of Smart’s glorifying prose, but no less masterful. Patel subverts all expectations for the genre: there is no beginning, middle, or end to this affair. The story is presented non-chronologically; we see the narrator and the man she is obsessed with (again unnamed) as they circle each other, push and pull, start and stop, over and over again. He is openly narcissistic, and he has no qualms about discussing his extramarital affairs with our alienated narrator, who accepts every crumb of attention from this worldly, powerful man. Here, obsession is not a gift to plumb for writerly inspiration: here, obsession takes the form of a married narcissist and his white influencer mistress, both of whom become the painful reminders for our lovelorn narrator of all the ways she is Othered by her race, class, and outsider status.

I’m a Fan reads like an inevitable conclusion, or perhaps just another stepping stone, in the genealogy of a woman scorned, marked by an era wherein sexual surveillance of both the self and others has become a naturalized aspect of being a citizen of the digital age. In fact, I’m a Fan reads as an updated version of the gender politics in The Possession, with only social stalking mechanisms improving between the two.

In the new social media landscape of 2023, Patel’s narrator is able to trace every minute of the influencer sleeping with the man she is obsessed with. The narrator mentions having friends, but we never see them on the page: in fact, we never see any dialogue or real interactions, we only observe her from a distance as she recounts it, as if in a deranged Twitter thread. The social media landscape, late capitalism, global warming, the economy, race relations, gender politics: it’s all important, and it’s all a distraction, and nothing gets done or changes. There is only shouting into the abyss.

Like Smart and Ernaux, Patel writes a narrator ravaged by love, but unlike her literary forebears, she writes a narrator willing to bite back. This is hardly a spoiler: I’m a Fan doesn’t just end, it spirals, launching off the rails but cutting us off at the point of impact. We don’t observe the aftermath, just the highlights, much like a viral moment online.

And what of the aftermath? Well, there was Smart, who raised four children as a single mother but found late-in-life success, surely surpassing George Barker’s own out-of-print legacy. Likewise, Ernaux, who has mined her affairs to brilliant effect and numerous literary accolades, was left with her prolific career as a Nobel Prize-winning novelist. But I’m a Fan asks whether the productive ends can justify the destructive means wherein a male muse overtakes the novelist, sublimating her totally in service of his own whims, leaving only the charred bones where love once stood. “I want to gain immortality because of my brain and not because of the potential of my womb,” Patel’s narrator decries.

The question is no longer whether love is enough; the question is whether it ever really was.

Be harlots, it hurts less.

The beautician and the baked vegetables by Vasundhara Singh

On Saturdays, the beautician takes a break from threading eyebrows to teach Anita how to make baked vegetables in a casserole. She learned the recipe in her home science class at college. A year away from graduating, she hopes to make enough money from threading eyebrows on weekends to afford to study in Delhi. Most of the women who visit her parlour studied geography or sociology at colleges in the city and then married civil servants and moved to smaller cities such as Chindwara (technically, it’s not a town but it is a town) to start nuclear families. Unlike these women, Anita is not a mother. Yet, that is. She is a housewife to a Police Officer, so it’s necessary to add the ‘yet.’

This is her second time going over to her house to teach the recipe. The first time did not go well. The batter was thick and lumpy and she fumbled with the buttons of the oven. Although there isn’t much for her to do. The cook diced and sliced vegetables. All she has to do is recite the recipe while whisking and mixing. Then, slide the casserole into the oven. The thirty-minute wait till the oven sounds a ting is the hard part of her visit: it’s when she is forced to sip tea with Anita and listen to her talk.

Anita stares at the vegetables on the kitchen counter. Shabbily sliced capsicums, florets of cauliflower, diced French beans. The carrots, she remembers. The cook forgot to chop up carrots. He’s at the mandi and she’s never chopped a carrot before. She takes the bluntest knife from the penholder and begins at the tip and stops. The carrot has to be washed first.

Her armpits are damp and itchy. This time she starts at the thick end, but the carrot is hard as an infected toenail. She is sure the cook is smoking a beedi at some roadside stall. The doorbell rings. The knife is jammed in the carrot. She blinks furiously to stop tears from pouring out. As the beautician walks into the kitchen, she throws the carrot with the knife still stuck in it into the dustbin. Turning around, she says, ‘is it alright if we don’t add carrots?’

She is sautéing vegetables with Anita yapping at her side. She is talking about her husband’s brother, who will visit them from Edinburgh. ‘It’s a city in Scotland,’ she says. ‘It’s alright without the carrots, right?’

‘It is, madam,’ the beautician assures her, but she grows nervous and scratches her forehead.

‘Are you sure? I don’t want him to think I haven’t added enough vegetables.’

All this chopping and sautéing is being done for her husband’s Edinburgh brother. She doesn’t want him to think that all they eat is rice and lentils even though rice and lentils is all they ever eat. Shubham has a weak stomach and prefers to eat light. ‘He should know that his sister-in-law is as cultured as any Edinburgh resident,’ she says.

Holding in her giggles, the beautician thinks how the woman looks like an overdressed girl, with long sideburns and a maroon bindi in the centre of her forehead.‘Well,’ she says, sprinkling salt over the vegetables. ‘If you had mushrooms, the dish would be top class.’ ‘Mushrooms?’ Anita says.

‘You should use extra virgin olive oil, not mustard oil.’

‘Olive oil?’

‘And if you get mozzarella cheese, then toh, the dish will be my god! Amul cheese isn’t stretchy.’

‘Maujirella?’

‘Mod-zee-rella,’ she says and slides the vegetables onto a steel plate. Anita’s nervousness heightens. She moves her head from side to side like a lost goat. The beautician hands her the bowl of flour, water, and milk to mix till she returns from the toilet. Latching the door shut, she bursts into soundless giggles. In the mirror, she sees her pink face. The dish can be made without mushrooms and olive oil, but she had fun watching Anita shake like a shitting dog. When she returns to the kitchen, Anita is stooped over the counter, scribbling in a notepad.

‘How do you spell maujirella?’ she says.

The beautician notices that the bowl of dry ingredients hasn’t been mixed.

The thirty-minute wait begins and the women sip tea in the drawing room. Anita envies the petite figure of the girl. It’s the figure girls of a certain class are gifted with. Not enough money to dine outside, not enough ghee to drizzle over rice and lentils. Anita knows the tea is too sweet, but won’t apologise for it. She’s embarrassed herself enough for the day. Olive oil she doesn’t know, but she remembers seeing mushrooms at Mrs Rajshri’s dinner party. She avoided mushrooms then, they didn’t look pretty enough to eat. ‘Aren’t your parents looking for a boy for you?’ she says to the girl, who is busy looking at the framed watercolour on the wall.

‘My parents are dead. My aunt brought me up. She is in the village.’

‘Haye! Haye! How did they die?’ she says.

‘Train accident. All fifteen people in the carriage died.’

‘God has his own plans,’ she says. A silence follows. She can’t think of anything to say, so she apologises for the tea being very sweet.

‘It’s fine. I like sugar.’

Such girls eat whatever they want and never grow fat, she thinks. She hates how her mother fed her ghee and cashews morning, noon and night. The beautician returns the empty cup on the tray and asks if she should come next Saturday. ‘Yes yes,’ Anita says. ‘I’ll get mushrooms by then.’

Upon her return from Anita’s place, she sees Meghna Madam waiting at the locked entrance. With her sling bag and braided hair, she looks every inch of the school teacher she is. The second she sees the beautician, she says, ‘what is this? I’ve been waiting for twenty minutes. Don’t you have a work ethic?’

‘Sorry Madam,’ she says and takes the key out of her jeans pocket.

‘Mozzarella?’ Shubham says at the dining table. Anita tells him it’s a kind of cheese.

‘I need it for the baked vegetables,’ she says.

‘Baked vegetables?’ he says, cupping a ball of rice and lentils. She tells him of her plan to feed baked vegetables to his Edinburgh brother.

‘He may live in Edinburgh, but his heart belongs to Uttar Pradesh. When he’s here, all he wants is rice and lentils, rice and lentils,’ he says, scooping out another serving of rice onto his plate. She slides her list of ambitious ingredients to his elbow and compliments his moustache.

In the morning, she finds the paper crumpled up on the floor.

At Mrs Rajshri’s place, Anita feels nauseous from the smell of unflushed urine. Her three twenty-something sons still live here, all college-educated and unemployed. Mrs Rajshri is surprised to find out that she served mushrooms at her party. She calls out to the cook. He confirms that mushrooms and peas were part of the menu.

‘Where did you get the mushrooms from?’ Anita says. He says that a man named Kamal sells mushrooms at the mandi.

‘Not always,’ the cook adds. ‘Only when he sells enough hash.’ Mrs Rajshri dismisses him and asks her why she is after mushrooms. She tells her of her plan to feed baked vegetables to her Edinburgh brother-in-law.

‘Very good! These NRIs should know that even we can bake our vegetables,’ Mrs Rajshri says.

When she asks about mozzarella cheese, Mrs Rajshri calls out to her cook who gives her the address of a Chinese restaurant that uses mozzarella cheese. ‘But,’ the cook adds. ‘The manager there refuses to accept any bribe except for half a kilogram of chicken thighs.’

Anita sends her cook to Kamal at the mandi for mushrooms and then to the butcher for chicken thighs that will be exchanged at the Chinese restaurant for a packet of mozzarella cheese. Three hours and sixteen minutes later, she is holding mushrooms in one hand and mozzarella in the other. The extra virgin olive oil has slipped her mind.

The beauty parlour on Sunday evening is flush with the shrill chatter of women. The girl attends to them one by one. Threading the eyebrows of Mrs My-Father-Was-in-the-Army who is currently sharing a story of how her father once escorted Indira Gandhi around a cantonment. When she massages Mrs My-Son-Lives-in-London’s feet, she hears of how her son prefers Indian tea over English tea. Mrs My-Husband-Has-High-Cholesterol cuts her off to point out that even the English prefer Indian tea over their tea bag in water nonsense. The girl goes around the room, threading and massaging and waxing and sighing. She pities these women, pities their lonesome and worthless lives and yet, she knows that in their eyes, she is beyond the realm of pity, an orphan who attends to body hair.

When Mrs My-Husband-Has-High-Cholesterol talks about Anita and her quest for mushrooms, the girl’s attention is diverted. She says, ‘poor young wife trying to impress her husband. These men only want rice and lentils, rice and lentils. Give it a few more years when she has children and her husband has high cholesterol. Then mushrooms will vanish from her mind.’

‘But didi,’ Mrs My-Son-Lives-in-London says. ‘Didn’t you serve mushrooms at your party?’

‘I didn’t know I did. My cook bought it from Kamal at the mandi…’

The girl’s pity transfers over to Anita and her worthless and lonesome quest for mushrooms. Her baked vegetables, prepared with mustard oil and Amul cheese. Let them pity her, she decides. She knows how to pronounce mozzarella and knows, too, the elegance of mushrooms. Once these wide-bottomed women are driven back to their husbands, who eat nothing but rice and lentils, the girl slides out a wad of cash from her jeans pocket. Nine hundred and eighty-five rupees. Mrs My-Father-Was-in-the-Army tipped her a hundred rupees. She has been generous ever since her daughter’s fiancé (an Army man, of course) lost his father to cancer last month, so the washing machine is no longer part of the dowry. Generosity pours out of her too and she decides to visit Kamal at the mandi.

Idling around the drawing room, while her husband idles around his office, Anita examines a white button mushroom. She bites off the cap. At first, it tastes like soil and then, it tastes like nothing. She imagines her Edinburgh brother-in-law scooping up a bite of the baked vegetables and taking a moment to admire its diverse filling before saying, ‘you’ve added mushrooms in this. Truly extraordinary.’ Then, he will scold Shubham for eating rice and lentils when his wife has made baked vegetables with mushrooms. Then, she will point out that she hasn’t used ordinary cheese but mod-zee-rella cheese. Oh, my. There will be applause. She will blush and turn to her husband to say, ‘do you still want to eat rice and lentils?’

She jumps in delight. She has forgotten the extra virgin olive oil.

A cow lifts its tail to piss on the pavement. Fake pearls hang from the earlobe of a woman bargaining with Kamal at the mandi. She is certain the karela should be half its price. Kamal is certain that the woman thinks he was born yesterday. This goes on for five minutes and the woman is forced to buy karela at its original price. It’s the beautician’s turn now. In a conspiratorial voice, she asks for mushrooms. Kamal examines her breasts and frowns. They’re small as lemons and she knows this. He says, ‘beti, I have a packet left but mushrooms are costly. Do you want karela?’

‘I know all about mushrooms,’ she says, raising her chin. ‘For how much?’ ‘Five hundred.’

‘Five hundred,’ she says as piss collects in her underwear.

‘So karela then?’

She presses her thighs together and says, ‘mushrooms aren’t for five hundred. You’re fooling me.’

‘You’re fooling yourself, beti. Is this much karela enough or should I add more?’ A woman in a turquoise sari with a servant following behind her arrives at the stall. She points with a sleek finger at the items she wants. Karela isn’t one of them. Kamal obediently attends to her without forcing her to buy karela. The servant steps forward to take the polythene bags. In a confident voice, the woman asks for mushrooms. As he is handing her the packet, the girl says, ‘the mushrooms are mine.’ The woman smirks and asks if there is another packet.

‘Only one,’ he says, glaring at the girl who feels hot from the overhead sun and cold from the piss.

‘Five hundred,’ the girl says and slides a trembling hand into her jeans pocket. ‘No, no, beti. Children nowadays are hard of hearing. These are top-class mushrooms. Six hundred rupees.’

More piss collects in her underwear. After a moment of standing still, the woman opens the clasp of her leather wallet. The click of the clasp is the sound of pity. The girl takes the wad of cash out of her pocket and pays Kamal six hundred rupees. The wad of cash is no longer a wad. The cow is still there, still pissing.

Anita is surprised to see the beautician at her doorstep on a Monday afternoon. Sweat and spit swim in the pit of her upper lip. A school backpack hunches her shoulders. Poor girl, she thinks, how hard she works and for what, a few hundred rupees. Even though she welcomes her in with a smile, Monday is not a good day for distractions. Monday is when she instructs the servants to replace the stained newspapers from shelves and drawers with fresh ones. She must stand and watch them do this, otherwise they will run off to smoke a beedi behind the hibiscus bush. The girl is grinning as she takes out a packet of mushrooms from her bag and hands it to Anita who shouts for her cook and asks him to bring the items he bought yesterday.

‘Especial items?’ The cook says, and she nods with proud, wide eyes. He places packets of mozzarella and mushrooms on the centre table.

The girl looks on with nervous, narrowing eyes. Anita tells her about Kamal at the mandi and the bribe of chicken thighs. She wipes the sweat and spit from her upper lip and says, ‘how much for the mushrooms?’

She shouts for the cook and asks him the price of the mushrooms. ‘Four hundred and fifty I got it for. Though, he said he won’t sell it for less than five hundred. Chutiya sala.’ She tells him to clear the dirty newspapers from the cutlery cupboard.

The girl sinks into the sofa and mutters, ‘chutiya sala.’

Oh, Anita thinks, the poor hard-working girl is here to collect her fee. She tells her to wait while she counts the slim bundle of notes kept in a steel bowl on the oven. There are three ten rupee notes and a five hundred rupees note. She returns the ten rupee notes to the bowl and takes the five hundred to the cook who leans against the cutlery cupboard, dreaming of the hibiscus bush. ‘Should I give her five hundred?’ she says.

‘For what?’

‘Baked vegetables.’

The cook smirks. Poor rich woman, he thinks, how foolish she is.

She feels like a fool. She, an orphan who attends to body hair, has no business buying mushrooms. All she is good for is listening to Mrs My-Son-Lives-in-London talk about her trip to Oxfordshire where she ate her life’s softest Gulab Jamun or Mrs My-Father-Was-in-the-Army bitch about her daughter’s fiancé. ‘He has a mole on his right earlobe. You know what that means. Chronic constipation,’ she said. When Anita hands her three hundred rupees, the girl doesn’t know if she should thank her or spit in her face.

Anita returns her mushrooms. ‘Take this. I have mushrooms already. You can sauté it with onions and chillies. I read that in the Tarla Dalal cookbook.’ The girl hopes that the woman and her Edinburgh brother-in-law get loose motions after eating baked vegetables. ‘You don’t need to come on Saturday,’ she says. ‘I’ll manage on my own.’ Doesn’t know how to pronounce mozzarella and thinks she can manage on her own, the beautician thinks as she shoves the mushrooms into her backpack.

When Anita hands her three hundred rupees, the girl doesn’t know if she should thank her or spit in her face.

‘You forced me to buy mushrooms,’ she says to Kamal at the mandi. He is unhooking the tarpaulin roof above a dishevelled display of vegetables.

‘Beti, you must think I was born yesterday,’ he says, twirling the hair growing out of his ear. The mandi is closing for the day and the last of the housewives are buying ladyfingers to eat with rice and lentils. Folding the tarpaulin, he says, ‘I told you to buy karela, beti. But you wanted mushrooms. What were you planning to do with them?’

‘Sauté with onions and chillies,’ she says, watching him dump the day’s unsold vegetables into a polythene bag. ‘Take these back and give me three hundred rupees.’ He looks at her lemon-sized breasts and frowns. ‘The mushrooms cost six hundred,’ he says. ‘Why ask for three hundred?’

‘I know you won’t give me six hundred,’ she says as piss trickles down her thighs. He switches off the mustard bulb and says in the darkness, ‘I won’t give you three hundred either. Now shove these mushrooms into your mother’s behind.’ ‘I can’t shove these mushrooms into my mother’s behind. She is dead,’ she says in the darkness, breathing in the scent of sandalwood and the smell of piss. He switches on the mustard bulb and sits on an upturned plastic crate. She stares down at the white button mushrooms and feels so absolutely alone that even tears refuse to soothe her. He passes her a lit beedi and she takes a drag.

‘What’s the deal with mushrooms?’ he says.

‘You tell me,’ she says and blows out a ribbon of smoke.

Anita’s Edinburgh brother-in-law is bathing. He said that he hasn’t bathed with a bucket and mug in three years. She is disappointed that he doesn’t speak with an accent, but she saw the driver carry a family pack of toilet paper into his bedroom. She runs a hand over the capsicum and cauliflower and carrot and whispers to the smooth white batter, ‘you look like heaven.’ The diced mushrooms and grated mozzarella are kept in separate bowls. ‘Is dinner ready?’ her husband yells from the drawing room.

‘In thirty minutes,’ she yells.

‘I’m sacrificing my stomach for your baked vegetables,’ he yells and laughs. ‘Mod-zee-rella, mod-zee-rella,’ she practises the pronunciation.

She is looking at her Edinburgh brother-in-law eying the lid of the casserole, the casserole of baked vegetables. In a moment, she will serve him the gooey, crusty, stretchy marvel and then he will look at her with awe. Her husband yawns and lifts the lid. She scoops out large servings onto their plates and takes a deep breath before saying, ‘baked vegetables with mushrooms and mod-zee-rella.’ Her brother-in-law looks at his yawning brother with strained eyebrows.

‘I am lactose intolerant,’ he says.

‘What intolerant?’ she says.

‘I can’t eat dairy. This is cheese.’

Shubham, struggling with the elastic cheese, says, ‘I told you to make rice and lentils.’ She gets up from the chair and tells the cook to prepare rice and lentils. She apologises to the men for the baked vegetables and places the heavy casserole into the oven, as if sweeping dust under a carpet.

At midnight, she tiptoes to the kitchen and takes the casserole to the dining table. She dips a spoon into its cold crust and tastes the mushrooms and capsicum and mozzarella. As she swallows her masterpiece, she feels absolutely alone.

Under the Summer Sun by Cait Barlowe

It’s the beginning of September, and the hot, orange sun hangs heavy in the sky. The leaves are holding on tight to their summer colours. The breeze is cool in the evening, the moon bright and hopeful. I find myself anxious in this transition between seasons, excited for the fall yet mourning the summer.

This playlist touches on feelings of change, introspection and transformation. To me, this playlist embodies the desperate longing for what has passed and yearning for what is to come. These songs feel like the end of the summer and I like to listen to them while I ride my bike along the river, even sometimes singing out loud. I hope you enjoy and find something within this playlist that speaks to you. —

The Vows by Andrea Bass |

I’ll show up at 2:00 a.m.

with an armful of peonies.

I’ll celebrate you and cry

with you. I’ll summon a future

where we talk about our days

into the night. The nights

spill into mornings, so groggy, so bright,

the coffee never strong enough.

You can see my hair when I wake up.

I’ll brush yours, careful

where it’s tangled. I’m not a hugger,

but I’ll hold you if you need it.

I’ll take your hand and squeeze it

underneath a table. I’ll lock eyes

across the room and roll them

when you do, when the same man

makes the same joke that’s never been funny.

I’ll look beautiful for you, I’ll look messy

for you, I’ll look for goodness

in your scars. I’ll tell you

who you are when you forget.

I’ll cuddle your babies

and ask for pictures, in love

with their sweet faces and pudgy thighs.

I’ll put a ring on your finger

and pledge forever, so many brides

coming down the aisle in their white

dresses, saying “I do” to the ones

they’ve laughed with for decades.

Let’s spend the rest of our lives

loving and cheering and grieving

and hoping the vows somehow hold.

Thank you for reading paloma, a casual, monthly art and literature magazine. If you’d like to submit work, you can find our submission guide here. You can also find us on Twitter and Instagram. Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓

Beautiful first issue! Congratulations 🥳

Congratulations