Welcome to ISSUE 007: PASS ME THE SPOON 🥄

“Will you do me a favour,” writes Rocío Díaz, “will you kick me out of this party?”

The month’s issue centres performance, desire, and relationships in every form, from mothers and daughters on holiday in Vasundhara Singh’s short story, to a wife playing pretend in Amani Hope’s flash fiction. In a poem named for the Cantonese romanization of moon, keiyi reflects, “I sit at the roundtable of women who have lost their names to husbands.” “Burrow deeper and never let me claw you out,” writes Amani.

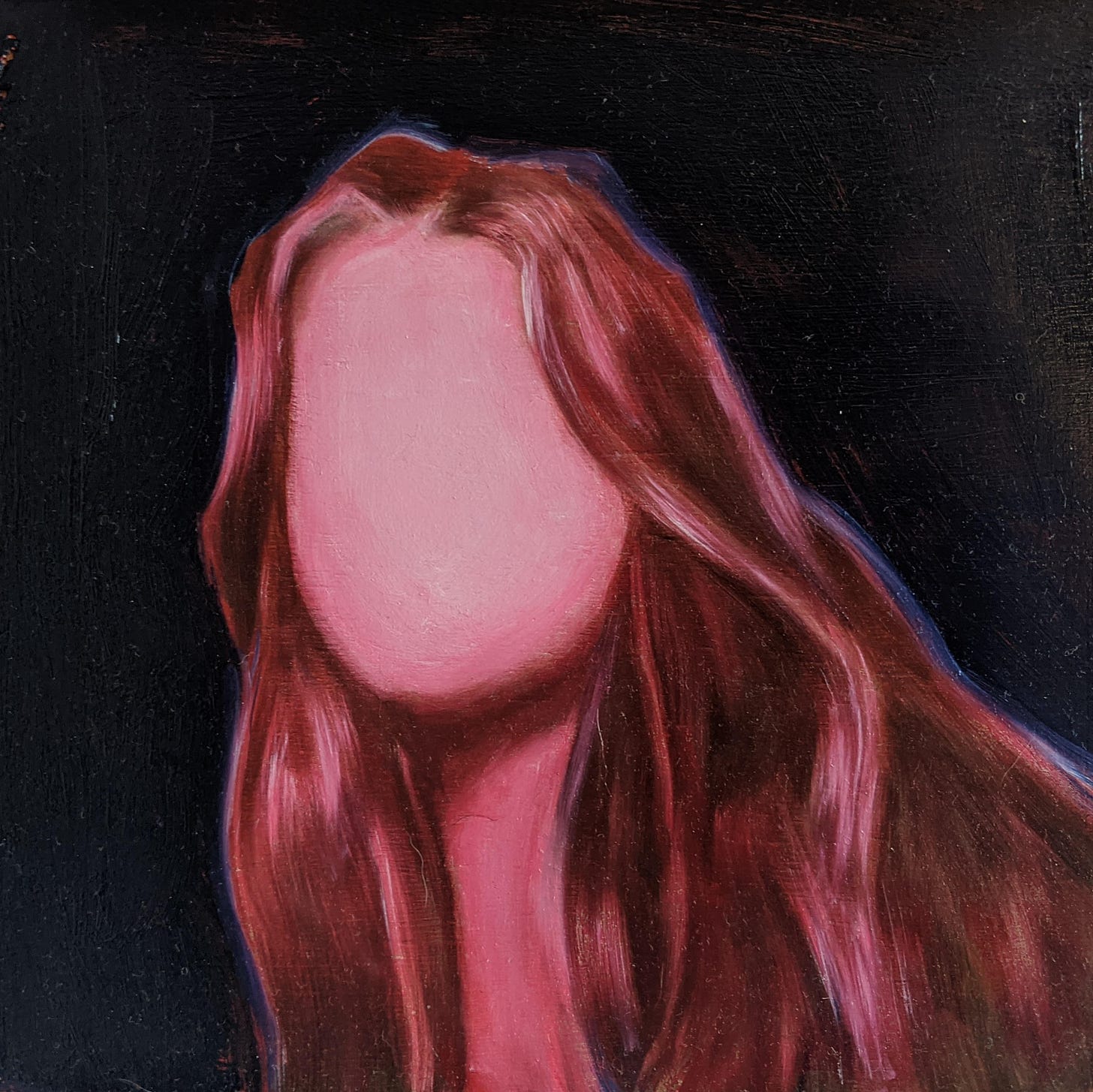

Then, Isabelle Kosteniuk contributes two hauntingly reflective oil paintings, and Nirris Nagendrarajah brings us the latest from the Sundance Film Festival. “Pass me the spoon and reflect,” writes Nilay Conraud in this month’s titular poem, burrowing deeper. Speaking of Nilay, we are thrilled to announce that she has joined the paloma team as our new Poetry Editor!

“Nilay works in the film industry as a script supervisor by day and as an English editor by night, or vice versa. Either way, she is a carer and defender of text. She is based between France and Canada and writes poetry and fiction in English, French and Spanish.”

Please join us in welcoming Nilay, and dig deeper into ISSUE 007. Enjoy.

| co-editor

The Husband Knows I’m a Fish by Amani Hope [Flash Fiction]

Pendent Reflection and Kelsey by Isabelle Kosteniuk [Visual Art]

Damn, I Love You by Amani Hope [Poetry]

Mrs Singh, where will you sleep? by Vasundhara Singh [Fiction]

the party by Rocío Díaz [Poetry]

Pass me the spoon by Nilay Conraud [Poetry]

Being Serious: All the Highlights from Sundance 2024 by Nirris Nagendrarajah [Non-Fiction; Culture]

The Husband Knows I’m a Fish by Amani Hope | Substack

When the husband has friends over, I pretend I’m a wife. I do things for him like human females do and try to impress him. Today, his friends tinker in the garage with a soldering tool, melting and bending metal to their will. The husband calls them the boys. I run out and say, “Hey boys, what are you up to in here? Are you hungry? I can make you bagels and cream cheese.” Which they deny saying it’s too late in the evening for bagels, and they ask me to cook them something hot. “I love to cook,” I say. I order Russian food on the delivery app, and thirty minutes later the doorbell rings. I place everything onto a tray and bring them bowls of soup, blini with caviar, herring and other beebobs like pickles. My fine ceramics clink together with such charm. “I whipped up some borscht for my boys out here in the garage,” I say. “And fish!” “What’s that on your head?” The husband says. I’m wearing a scarf around my head now, like a babushka. I wrapped it over my hair and tied it under my chin while I was waiting for the food. It was nice having a moment to ogle at myself in the mirror. I also put on a pink apron. “Gotta keep all the hairs nice and tidy. You know that.” I say. “Anyways, I got the chills.” The sun is going down behind our fence and the sky is paling blue. The husband puts his hands up like he didn’t mean to ask questions or even utter a word. I stand to the side and watch the boys devour their soups and knickknacks, dipping crusty bread into whatever purple mess and oily bits. When they’re done gobbling, I pluck the crumbs from their laps and wipe their chins with their napkins. I stack every bowl onto the tray so they can marvel at my talents as I walk away. I can feel their eyes on me. I hear one of the boys say, “That’s a good one,” to the husband. The husband replies and says, “She’s a keeper,” or maybe he says, “She’s a kipper.” I’m not sure.

jyut6 by keiyi | Substack | Instagram

the moon is ripe and molten silver and I sit at the roundtable of women who have lost their names to husbands they who poured glittering gold coins down gutters whose fists married black and blue to the cheeks of their wives who lie in the foreign beds of young girls white as unblossomed lilies 中秋節快樂! I sit with the moon knowing when the waves ebb I too must fade into the shadow of the sun. you would eat tongyuen without any filling which was diabolical to me so you could relish the wholeness of it? feel it clench and unclench– sink your teeth into virgin ripeness without surprise you said it was just like swallowing the moon but what about the woman living there? and the family of rabbits and the man who with Sisyphean effort chops down a tree night after night after night it sprouts from silicone, vengeance its seed— you swallow iron and shadows. you swallow glutinous flour and water my mother told me ‘that’s all it takes to make daughters’ we can make as many as you want baby I’ll swallow your seed as long as they find roots in my stomach and we will grow in the light of the sun up your gullet, glowing we used to glow together twin mirrors when you put two mirrors together infinity appears, the space in between is where the infinite tenderness of the universe resides shy like the moon’s pale underbelly soft as a memory of shorter hair the smell of soap cowering behind my salt-scented mother girls running infinite circles around each other until they disappear in a stream of serendipitous silver where are you now? it would take an eclipse to save us our big toes over the line we are ready to combust the glorious death of stars oh yes I would have to take you into my mouth and swallow you whole

Pendent Reflection by Isabelle Kosteniuk | Instagram

Kelsey by Isabelle Kosteniuk

Damn, I Love You by Amani Hope | Substack

Pants are unbecoming Put them on the floor and Take a step towards me We’re in the darkness And I’m reaching for you Always reaching and spreading My fingertips over your skin and Through your hair but grabbing at The strands and pulling you inside me Where my legs are open but also Deeper where angels run me over With their giant breasted wings like a Crash of air they whip at me And sting my skin with every breath My cheek left blushed and glistening And I pull you into a place smaller And deeper where only you’re allowed to go You must stay there forever You must be enclosed in those dark walls In darkness inside me where I clutch my hands on my heart You must burrow deeper And never let me claw you out

Mrs Singh, where will you sleep? by Vasundhara Singh

The last time Mrs Singh saw a bathroom this elegant, she was dressed in a beige uniform, staring at the toilet bowl with a bucket in her hand. The last time Mrs Singh was in a resort this beautiful, she was working there, beige uniform and hair swept in a tight bun. She looks at her daughter, standing at the reception, arguing, in perfect English, with the manager. “Where will my mother sleep?” she barks with raised brows, “on the floor?” The manager replies, “ Madam, we can put a single bed for her.” Mrs Singh watches as a lone teardrop slides down her daughter's bronzed cheek. Her son-in-law pats her lower back. The son-in-law had mistakenly booked the suite with a single bedroom. He claims that he was misled by the information on the website. “Mumma,” the daughter says, “you don’t mind sleeping on the sofa, na?” “Not at all, beta,” she replies, “have you eaten anything since morning? You look so weak.” Mrs Singh was a 29-year-old widow with a five year old daughter when she began working at the Grand Vision resort at Bandhavgarh. Her late husband’s uncle had found her employment there. Her quarter was a single bedroom with a single window. Her daughter studied at the local government school while she changed stained bedsheets and made swans out of towels. They ate leftovers from the complimentary breakfast and used the community bathroom. Mrs Singh and her daughter shared the same bed until she was eleven but in her twelfth year, Mrs Singh gathered all her savings and sent her off to a private residential school and while her daughter studied, Mrs Singh changed stained bedsheets and made swans out of towels. Mrs Singh can hear forks scratching against plates and wine glasses making a tink-tink. Her daughter and son-in-law are discussing whether they should try the green Thai curry or the barbeque prawns. A Russian woman feeds baby corn to her toddler at the next table. Her daughter returns with two plates and places one in front of her mother—a garlic naan, cottage cheese in red gravy and Dal Makhani. Mrs Singh asks them if they would like to visit the Shanta Durga Temple in the evening. While the son-in-law looks up, wide-eyed, her daughter smirks and says, “mumma, we haven’t paid three Lakhs for five nights just so we can visit some stupid temple.” Mrs Singh takes a bite of her garlic naan. In the suite, her daughter admires the size of the sofa. “Mumma, you will fit here so easily. Chalo, that’s one problem solved.” At half past four, after they leave for the pool, Mrs Singh sits on the sofa for half a minute before putting on her loafers and heading off to the Shanta Durga temple. The temple is situated in a narrow building with marble floors and a wooden roof. The devotees, mostly women, stand in a line, awaiting a glimpse of the goddess. Mrs Singh stands at the very end, behind a woman in a chiffon saree. The priests wearing dhotis lift the curtains for fifteen seconds at a time and the women balance on their tippy toes while chanting a hymn. The deity of Shanta Durga looks nothing like her counterpart, Kali Maa. Her eyes are kind and she is flanked on either side by round cheeked boys. She is the perfect woman—pure, patient and fertile. The curtain drops. The hymn continues. The woman in the chiffon sari turns to ask Mrs Singh, “you’re from Pune?” She shakes her head. “A tourist then?” She nods. “We visit every year. My daughter’s father-in-law is the head priest. And, do you know what is absurd?” Mrs Singh bites her upper lip. “Thirty years ago, I had asked Maa Shanta for a daughter.” The curtain is raised. The hymn grows louder. Mrs Singh prays that her daughter may never have to sleep on a single bed with a widow that frames a compost pit. At the entrance, under an arched gate, she searches for her loafers from among a sea of flip flops and sneakers.She is startled by a woman’s voice. “You shouldn’t wear black to the temple,” says the woman in the chiffon saree. Mrs Singh mumbles an apology. The woman hands her a lotus, pink and fleshy. “Take this,” she says, “may Maa Shanta Durga protect you.” On her walk back to the resort, in the golden glow of dusk, Mrs Singh remembers the last time she wore this saree. It was the day her daughter received her PhD in English Literature from the University of Delhi. She can't recall the long and complicated title of her thesis. This saree had cost her fifteen hundred bucks and she had beamed when her daughter said, “you look just like the other mothers.” The suite is quiet and dark. Her daughter and son-in-law are fast asleep in their bed. Mrs Singh leaves the lotus at her daughter’s feet and lies down on the sofa in the living room. From the window, she sees a cloudless sky.

the party by Rocío Díaz | Instagram | Medium

here’s what you should know about the parties I’ve attended: it’s really just one party and I wasn’t invited at all these facts don’t make its plurality or the possibility of being invited to them any less real these parties are beyond logic here, what’s true and what’s false converse casually in the kitchen squeezing against each other when someone opens the fridge door suddenly so close their breaths become indistinguishable from one another anyway, I’ve been to the party but I am also perpetually getting ready for it and simultaneously trying to leave it then again, no one seems to leave early they chase the bluest circle of the dawn there is plenty of people there already (even though it’s just started and has been going on for hours) with long faces and geometrical noses, kaleidoscopic eyes hungry for your presence eager for the sound your skin makes feasting on the air your voice emanates I am too mesmerized, I mean by the sheer size of this get-together impossibly brief and immeasurably long hours upon hours of longing stares, growing pains, desperate traffic jam-like screams blunt sentences that could make thunder crawl back into its cave upsettingly quiet and disturbingly beautiful it’s a huge place and we are all smoking, but everyone calls the cigarettes a different name there are glass doors everywhere carpets on the floor made of overgrown grass couples fuck in the bathroom cabinets mothers smile at you from the couch and the boss of a job you could’ve had stares at you from the top of a narrow staircase frankly, I could’ve left the party plenty of times the stars know I’ve tried I’ve rejected the drinks and wished I was somewhere else I’ve batted my eyelashes at the older men hoping they’d take me away I hid in the bathroom for hours my eyes fixed on a spot in the ceiling, calling for some sort of divinity someone who should’ve put an end to this such a long time ago and at the same time I’ve danced frantically as if my feet could move so fast that my skin would fall off all in one piece like my dew-made soul, the one that leaks off the roof and dampens the walls I’ve chewed the ear off of strangers talking about oceans and trees that don’t exist here rather, on that place where daylight sits I’ve broken glasses and sat on beds with my shoes on said I’m sorry in hushed tones never really meaning it I’ve kissed people hard enough so that maybe they could’ve (—should’ve?) suffocated me instead they touch my hair and I think of a park bench somewhere far away where noise doesn’t exist where having a body doesn’t feel like punishment where fear isn’t the means, just the end just the end will you do me a favor? will you kick me out of this party? I’ve done my best, brought the cheapest wine and I know damn well I’m not at the center of it so who cares?

Pass me the spoon by Nilay Conraud | Substack

Pass me the spoon and reflect Your perfectly circular Iris And your particularly pointy Tooth Scrape what’s left of my soup In allergy-ridden posturing (any nuts in this?) To showcase just how delicate you are Well I’m seduced The night is indeed young and beyond now the elders stay home The blurred-eyed intuitive sleeper mistaking freckles for moles So pass me the spoon

Being Serious: All the Highlights from Sundance 2024 by Nirris Nagendrarajah | Substack | Twitter | Goodreads | Letterboxd

For a long time these words by the critic Tobi Haslett, from his essay on the writer Susan Sontag, have sat in my mind: “The point was to be serious about power and serious about pleasure: cherish literature, relish films, challenge domination, release yourself into the rapture of sexual need—but be thorough about it. ‘Seriousness is really a virtue for me,’ Sontag wrote in her journal after a night at the Paris opera. She was twenty-four. Decades later, and months before she died, she mounted a stage in South Africa to declare that all writers should ‘love words, agonize over sentences,’ ‘pay attention to the world,’ and, crucially, ‘be serious.’” Be serious: these two words have ruled my consciousnesses, day and night. In everything that I do—when I write, when I read, when I watch, when I listen, when I talk, when I think, when I pay attention, when I love—I try to be as serious as I can be, to live a life of the mind proper. And it is the quality that I look for, and admire, in other people, and in works of art too. How serious is this film, I wondered over the course of the five long days I attended online screenings of the 2024 Sundance Film Festival. Only the film could answer. Throughout the festival there were a few recurring themes: multiple chapters used as a structuring device, daddy issues, bald men, increased representation of trans identities, dream sequences, horses and dogs, smoking and drinking the pain away, and, most of all, grief. The first film I saw, Handling The Undead, which stars Renate Reinsve and Anders Danielsen Lie—is about three families grieving the loss of loved ones. There is the long-dead (a son/grandson) and the just-dead (a partner) and the about-to-die (a wife), but after a brief blackout they all flicker back to life: zombified. The most insightful moment in the otherwise thin, ambiguous script, which saves the most interesting development for the final minutes, occurs when the police knock on the door and ask if the dug-up body of the son is in the apartment. The grandfather, not wanting the lose his grandson again, instructs his daughter to say nothing. They’ve already lost him once; and they'll do whatever they can not to lose him again. The various layers of grief is echoed in Suncoast—a teen dramedy starring Nico Parker and Laura Linney—that tells of a white mother and her bi-racial daughter as they wait for their brain-dead son/brother to die in a hospice. The mother runs away from confronting the reality of the future; the daughter comes-of-age amongst her peers and tries to outrun her past; and for the entire movie the brother just lies there, a mere talking point for the ethics of assisted suicide. These films—in addition to Exhibiting Forgiveness, a bloated Barry Jenkins knock-off that feels more like a play—preach the necessity of letting go of loved ones, but not forgetting them. The act of remembering is the crux of A Real Pain—directed and starring Jesse Eisenberg, featuring an excellent performance by Kieran Culkin—where a severely neurotic, anxious and introverted man—Eisenberg, if you couldn’t guess—and his lively, manic-depressive cousin on the verge of a nervous breakdown fulfill their late grandmother’s request and go to Poland to join a Holocaust tour. It sounds grim but it’s actually light, funny, witty without being pretentious, peaceful and briskly paced. There’s a scene near the end where Culkin’s character suggests they all place a rock atop a tombstone so that the dead know they are not forgotten; then, when they visit their grandmother’s home, they try to place stones at her doorstep but a nosy neighbour tells then they can’t; and in the end, before Eisenberg’s character returns to his walk-up, he places a stone on his porch. “You are not forgotten,” this film says. Contending with one’s Jewish heritage is also at the heart of Between the Temples—which stars Jason Schwartzman and Carol Kane, who have insane chemistry—and was shot by The Sweet Easts’ Sean Price Williams. In it, a cantor whose life imploded after the death of his literary wife runs into his old music teacher who wishes to have a bat mitzvah. John Magary’s editing gives this Alex Ross Perry-like film its own rhythm and unique frequency that, once you tune into you, you can fully immerse yourself in. It’s charming and slightly perverse, and the performances—Dolly De Leon’s in particular—are incredibly rich. A film like this knew how it wanted to be, which can’t be said of all the films of the festival. For instance, A New Kind of Wilderness—which won the World Documentary Jury Prize—has the depth of a YouTube short: it failed to have the poignancy it thought it was capturing, the subjects were rather unremarkable, and it was shoddy, rough, uneven. What were the stakes here, I kept asking. On the other hand, Layla perpetuates this brown-drag-queen/white boy trope that follows behind last year’s Unicorns and traps its protagonist—who doesn’t know their self-worth—in an age-old binary opposition: the cold, confining light of heteronormativity, or the vibrancy of a queer community. The end of the film, which is meant to be a triumphant dancing moment, recaps the most important scenes of the movie, just in case you forgot. I wish I had. Love Me, which stars Kristen Stewart and Steven Yuen as a buoy and a satellite who fall in love, is not as ground-breaking it thinks it is. It feels like the rock sequence in Everything Everywhere All At Once refracted through the Wall-E screenplay; but it’s preoccupied with critiquing social media and influencer culture and about 80% of this meagre satire is poorly-designed animation. It jumps back and forth through various dimensions (CGI, animated, live-action, YouTube vlog) and it loses itself in its own design, similar to In the Summers—which, for some reason, won the U.S. Dramatic Grand Jury Prize—which follows two daughters and their dead-beat father over the course of four summers. In unveiling a history before our eyes—shaped by binaries and archetypes and with the aesthetics of Andrea Arnold—the film tries to make a point about how some people grow and change while others can never bring themselves to be self-aware and self-satisfied. The content felt very juvenile, and the realism highly-staged. The attention In the Summers received made me begin to question the validity and authority of awards and juries. It became increasingly clear to me that my tastes and preferences and desires did not necessarily align with those of the juries, and that the films in which I found greatest artistic pleasure seemed not to have caught people’s attention at all. The narrative that was building itself in my head with each successive film told a unique story of its own. The best film I saw at the festival was A Brief History of a Family, directed by Jianjie Lin—a graduate of Tisch—shot by Jiahao Zhang and scored by Toke Brorson Odin. This film tells the story of a mysterious young man who becomes enfolded into a three-person family: first with the son, who is eager to make his acquaintance, then the mother, who had wanted another child but aborted it because of China’s one child policy, and finally the father, who longs to have someone talk to him about music and to be shown how to swing a racket or do calligraphy. It is almost as if all members of the family wish to possess this boy whom we know nothing about and who seems to have ulterior motives. From the first shot to the last, I was in its grasp, so patient it was, so restrained, and the sexual undertones between all the leads gave it a libido that most films lack these days. All the action happens beneath the surface—or extravagant tableaus, such as the one where one boy holds the other—Pieta-esque—under a spotlight—but the surface happens to have a sufficient amount of texture too. A twenty-first century Teorema. Other standouts include Black Box Diaries, where the journalist Shiori Ito adapts her survivor’s tale about sexual assault and the legal battle that ensued for the screen, creating an artful, raw, redemptive collage of footage that makes you go silent, brings tears to your eyes, and also evokes the sensation of a thriller. The stakes were real here. Only she could tell her story: and now—having told her truth—I’m interested in the stories that she tells about others. I was delightfully surprised by In the Land of Brothers. The film, directed by Alireza Ghasemi and Raha Amirfazli, tells three stories separated by 10 years, each which grapple with the nuanced dynamics between Afghan and Iranian communities. Sexual assault, fear of deportation, and the power of secrets and lies are explored here with such grace, such care, such artistry, and with such a talented cast that it awakens the senses despite the devastating subject matter. There are shades of Abbas Kiarostami and Asghar Farhadi here—especially the 2nd and 3rd chapters—but I’m excited to see what happens when this duo decide on telling a single story. The only other film that had an intelligent nervous system was Agent of Happiness, which primarily follows a man in Bhutan who is employed to go around conducting a survey for the country’s happiness index. The film hones in on the lives of the people he comes across; it digresses, and when it does, focusing on marginalized people such as a trans woman and the daughter of an alcoholic, it reveals that there are several people in the so-called “happiest country in the world” who are not happy at all and that this index is largely a farce. But the filmmakers—Arun Bhattari and Dorothy Zurbo—never explicitly state this; they embed it by way of editing, allowing us to come to this conclusion ourselves, and, at 94 minutes, it’s perfect. The last film I want to talk about is Sebastian, directed by Mikko Mäkelä, which follows a gay fiction writer who works as a freelancer for a literary magazine, has published a short story in Granta, and is working with his publisher on his debut novel. Lacking an imagination, Max anonymously puts a profile up online and becomes a sex worker, translating his experiences onto the page after long, hard showers. Max yearns for external validation; he is overwhelmed when one of his clients tells him he’s handsome and, unaccustomed to intimacy, he only sees sex as transactional. He’s bad at his job and is surprised when he’s unassigned from an interview of Bret Easton Ellis—his idol—and then fired. He puts little effort into his friendship with his token brown queer friend, but is shocked when it ends. One imagines what this film would’ve looked like if it wasn't so white, if the majority of the clients weren’t just older wealthy white men, if the climax of the film wasn’t getting locked out of a five-star hotel room in Amsterdam, if the lead had more of an emotional range. Sebastian is so concerned with self-exposure and vulnerability that it has multiple endings, doesn’t know where to end, yet could’ve been that much tighter if it did. It should’ve ended when Max goes from writing “he” and started writing “I;” when he no longer hid behind a fictional persona to tell his experiences, when he came out of the closet for himself, so to speak, but instead we get a book launch that ends as it begins: “Ask me anything.” But in all seriousness, as soon as the credits rolled, I found I had no questions.

Thank you for reading paloma, a monthly art and literature magazine. For information on submitting your work, please see the Submission Guide. You can find us on Twitter and Instagram. Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓

So excited to have a couple pieces published next to some incredible writers (in the best magazine ever might I add!)

Loved the Sundance review and how seriously it takes itself :)