Welcome to ISSUE 009: SORROW SEASON 🪱

That which lays dormant emerges–comes to life–in the spring. We cannot escape this at-times punishing reawakening. Katie Wolf’s collages try to turn memory into archive, all the while wondering, for whom? and why? Some of us, like Katie Haley in the fiction piece “Spring Is The Worst,” might wish we could bury the painful memories instead, defer introspection. Just like we must let spring run its course and bring life back from the winter slumber, the best we can do is surrender to our internal rhythms. “Worry will wear my features away”, writes Vice Sullivan in “Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior,” pointing at the most gruesome aspects of being one’s worst enemy. In their second poem in this issue, “In the Fields,” they want to love their way through “Sorrow, season and season again,” pertinently inspiring this issue’s title. Such is, perhaps, the nature of this time of year, with its contradictory pulls as we stand at the intersection of death and rebirth, pain and peace. Let us stand still and observe, and accept Mad Crawford’s invitation in “I live on the top of that hill” to have a peek through windows we “shouldn’t even look through”, hoping they might teach us something new, this time around. In Vasundhara Singh’s “The Last Woman of Gwalior,” you will be able to peer out “at the papery white bougainvillea swaying to a May breeze,” but don’t let appearances fool you, and pay close attention to the flowers this spring. Never forget that the cycle ends and renews, that ouroboric time circles back on itself, demands attention and confrontation. As Elliot Savin reminds us in “At the banshee club,” “This is what is natural / this is what is kind.” What is ‘this’ that is natural and kind, and how do we know it? Our editors’ minds are on Palestine; this spring calls for an end to occupation and instead the flourishing and self-determination of Palestinians. We stand with Palestine and with our comrades and friends acting in solidarity, using their writing and bodies as line of defense against genocide. As such, we invite contributions that speak to this political spring; we foresee liberation and we know that this is natural and kind; we know it to be inevitable like the coming of spring.

and | co-editors

At the banshee club by Elliot Savin [Poetry]

I live on the top of that hill by Mad Crawford [Poetry]

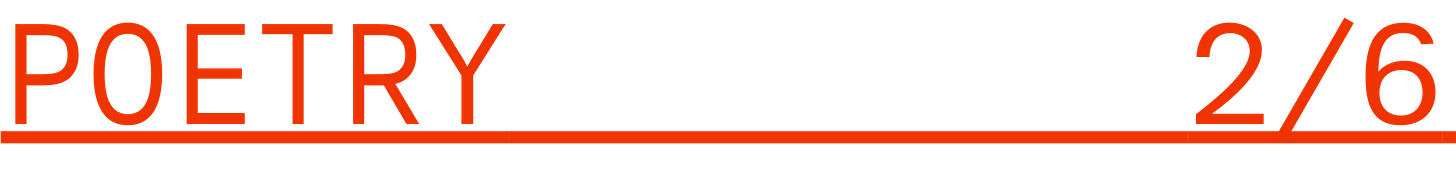

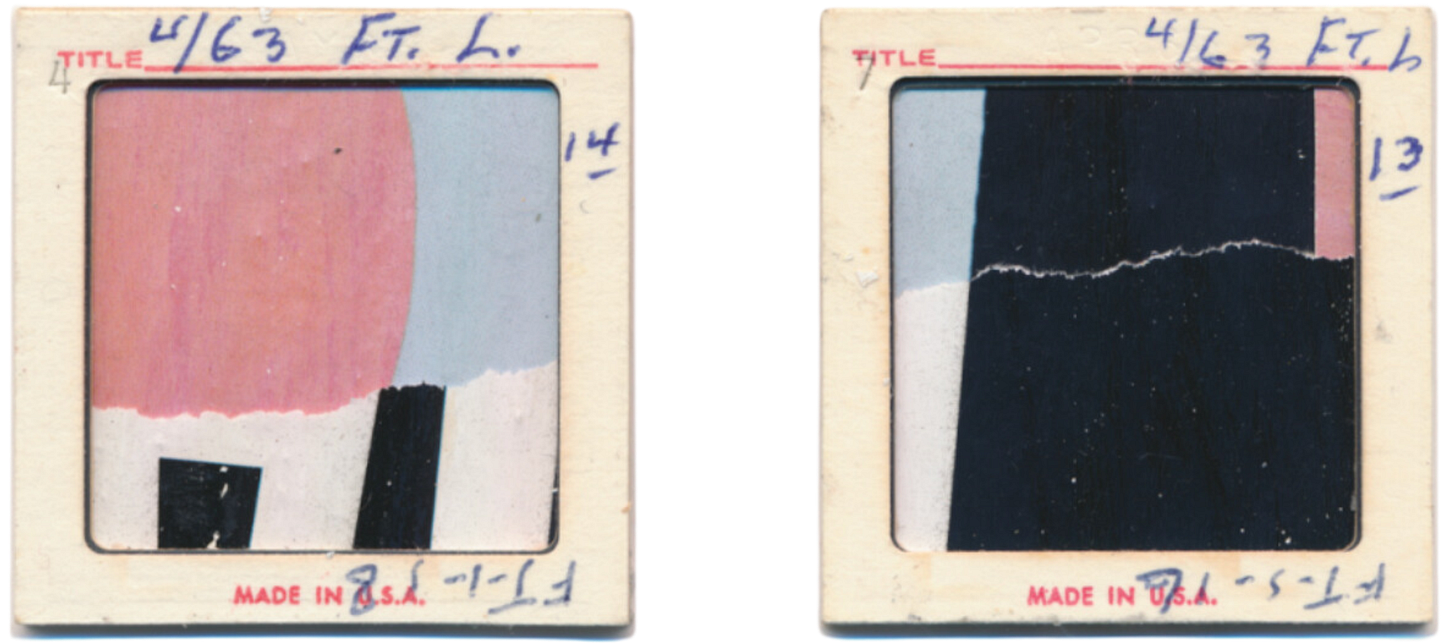

If Memory Serves Me and Hungry Eyes by Katie Wolf [Visual Art]

Spring Is The Worst by Katie Haley [Fiction]

In the Fields and Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior by Vice Sullivan [Poetry]

The Last Woman of Gwalior by Vasundhara Singh [Fiction]

At the banshee club by Elliot Savin

Last night at the banshee club my mother turned to me and asked if I could help her speak to the dead. We go back and forth like this often, my mother and I. She waits for me to step out onto the tangerine porch before she hurls the rain at my head. I don’t blame her anymore, not like I used to. Not like I used to when I could only write in my brightly flowered dress and had to sing for my dinner. I have learned to only look at her with my right eye, my good eye, lest I be disrespectful. So, we will summon the dead and dredge them up from where they sleep as the others wail around us. This is what is natural, this is what is kind. And while my mother presents them with the list of her grievances, I will prepare to leave on the first train tomorrow before the sun gets too high in the sky and I can look back and see what I have done.

I live on the top of that hill by Mad Crawford | Substack | Instagram

If Memory Serves Me by Katie Wolf | Website | Instagram

Hungry Eyes by Katie Wolf

Spring Is The Worst by Katie Haley | Instagram

Spring is the worst. The birds are back, the two that mate outside my window on the first day of sun each year. Last night their sex, five minutes at most, broke the branch they were doing it on. Then, post coital, they chirped for hours, screamed at each other until they couldn’t breathe. The bird that makes eye contact in the morning, who I am sure is the boy, stares, confused, waiting for my dad or brother to offer him a high five for the pipe he laid the night before. Instead, I stare back and tell him he kept me up. That the girl bird clearly hates him too otherwise she wouldn’t fly away from him the second the sun comes up. I tell him he’s the worst thing that’s ever lived, his feathers are ugly, and he probably lives outside my room because his parents didn’t want him. He shakes his head and wonders when I became such a prude.

Last weekend I got a sunburn in the Bay Area; spring is the worst. The leather from my purse strap dug in, dragged dry along my shoulder. After I got out of the sun and into my car I put Benadryl on a bug bite, too much. And kept the leg of my jeans rolled up to stop the cream from rubbing off. The denim was tight and the ointment smothered the bite until I couldn’t see the red anymore, bright white fluff with some leg hair poking through it. Keeping my leg up while driving made me sweat while the city was full of rich people and their goldendoodles anxiously waiting to get to a park. Dogs with mouths full of tennis balls leaned out the windows of cars that turned without signals. It was miserable. I hate bugs. All of them, even ladybugs. When my house was infested with them, I would gather as many as I could, thirty at once, and run outside to set them free while screaming at them to never come back. I was ten and thought they were the ugliest things I had ever seen. I hate spring.

I got Monistat from the pharmacy. The same tube I buy every March. I remembered to pick some up last night when I saw my thong had the same white stain as it does every March. After canceling a date on account of itching and burning, I walked towards the liquor store for food and more Benadryl since I had just used the last of it on another bug bite. As I turned the corner, the crosswalk lit with red from the neon signs of the store, I couldn’t see anything. My vision gets worse with lights, by nine at night I’m blind from flickering lights. At the store a man buys a case of hard lemonade even though there were no pedaling kids in the parking lot to buy it for. Freak. Spring is the worst. Once he leaves a woman steps up with a bag of candy in one hand while the other points at a pack of swishers behind the counter. On the walk home the cars blurred and the dogs barked. Spring is bullshit.

My mom throws up from accidentally swallowing the cream her dermatologist prescribed to get rid of her skin cancer. She’s a loud puker, a hacker. Dry heaves become screams. With the sound of her yelling and the splashing toilet water coming from the bathroom, I found out a kid I never met from the same college I dropped out of died. His round face, like a cherub, is everywhere on my phone with comments from hundreds of brothers promising paradise. Twenty-two and dead, waiting to be planted into the ground. I wonder if he was allergic to grass, if his new bed will give him a rash. If his mother is worried that the blanket they’re burying him with will make him too hot in the summer. If his father said I love you enough. I think about what his last order from the student bar was. A thirty two ounce dark beer; he needed it after his roommate pissed him off the night before by being too loud too late. A light beer with an open tab, first of many. Maybe a vodka soda with extra lime. I think about his ID, how many bouncers would see his birthday, a taurus. I think about his freshman year, what dorm hall he lived in. If we rode the same elevator, said excuse me on the stairs, held the door of the dining hall open for each other. As I get my mom a glass of water for her throat I think about Sam, that was his name. I think I miss him. Spring is the worst.

In the Fields by Vice Sullivan | Instagram

I want to live long enough to be loved by the shears of life season and season again, I want to love hard enough I never grow heavy with dust. Make me no martyr, no lamb, see me stand firm on my two legs with my ram’s horns hardened enough to bash a hole through sorrow. Sorrow, season and season again, and I am warm, sorrow, and I am unafraid of the stars above winking “come home, come home, come home”.

Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior by Vice Sullivan

Yesterday I chewed on the inside of my lip so badly it swelled up this morning like botched filler, full of writhing worries, little worms tugging at my face. The wound inside my mouth curves up to my cheek, copper taste and a paste of paling flesh, septic sore wrecked by my incisors. It’s like hunger is a fear, I hunger in terror tearing at my gums, my molars gnash and crash together behind pulled-tight lips glued together with spit, I have known this whole time it would not satiate but the jaw is the strongest muscle in the body and it will have its way with me and leave my face a masticated mess. Worry will wear my features away, and when my skin and my softness are gone worry will wear my teeth down to sand, pouring out of my mouth, a home for the worms.

The Last Woman of Gwalior by Vasundhara Singh

The old man, the ageless patriarch, sits at the long dining table, its mahogany wood capturing the reflection of the mustard bulb overhead. He says to his twenty-three-year-old grandson, “Your grandmother would have screamed at the sight of her beloved bungalow. How she loved each wall, every corner. Now look what’s become of it, of us.” He utters these words every evening, as the sun sets behind orange clouds and crickets clear their throats. The grandson, slightly chubby and pockmarked with acne scars, stands up from the cool marble floor and knocks at his father’s bedroom door. “Haan?” the father answers in a shrill tone.

“Papa, aren’t you going to eat dinner?”

As usual, a silence follows. The son knows his father will awaken at midnight and consume the last jar of heavy cream from Mr. Kabutar’s farm. He escorts the old man to his room, the one he shared with his dead wife. As the old man takes off his slippers and hauls himself up on the mattress, he declares to his grandson, “I hope tomorrow is my last day on Earth.” This, too, he is accustomed to hearing. He feels no pity for the old man for this land is flush with whimpering widowers. They don’t even have the option of marrying again for the Nari-Mahmari—or, the female epidemic—killed almost all of the country’s women. The tragedy, as some widowers will tell you, is that it took away the young ones first and left behind the aging lot who either died from old age or chronic exhaustion. A world without women is devoid of noise for the men have no one to complain to and no one to chide. Now they dwell in an eerie silence, chaste without choice.

On Sundays, the men of Gwalior gather at the Museum of Women which is housed in the erstwhile palace of the Scindia royals. The ground floor of the museum holds a photo exhibition of the various women that had once existed in the district, from the graceful Maharani to the humble homemaker. These photos were submitted by men on an online portal set up by the Government of India. The grandson and the old man admire the sly smile of a maid dusting the shelves of a rich man’s home. The father always refuses to accompany them not because the photos upset him or remind him of his premature widowhood. He has no interest in interacting with other wrinkling widowers who mope about, mumbling of their dead wives. On the first floor, items of women’s clothing are displayed behind glass cases—Chanderi sarees, Chikankari suits, Amritsari dupatta, silk petticoats and undergarments of cotton and nylon. Earlier, these were displayed on shelves for men to caress but when they began to masturbate, the garments were placed behind bulletproof glass. A sign that reads Gentlemen don’t masturbate is taped to the wall as one climbs the staircase to the first floor. Mr Srivastav sheds a tear every time he sees the sarees for they were taken from his shop which has since been converted into a grocery store. The old man speaks to Mr Kabutar, the great-grandson of the royal family’s treasurer and owner of the largest dairy farm in the district. “Sahib,” the old man asks in his croaking voice, “are you sure of the women returning?”

“A world without women is devoid of noise for the men have no one to complain to and no one to chide.”

“Arey bhaisaab, don’t you feel the humidity in the air? It’s never been so humid. I can feel their slender fingers down my neck.”

“And, what about the scientists? Will they ever work out a way to make men pregnant?” Mr. Kabutar frowns. “They tried with a few but failed. Some men died in their first trimester and others simply had swollen bellies but no babies.”

The grandson stares at an off-white bra, gazing at the delicate flowers stitched along its borders. He was seven years old when he last saw women, so it’s hard for him to imagine a woman’s touch. He remembers his mother’s untidy bun bobbing as she kneaded the dough in the kitchen and his grandmother’s snorting laugh as she milked the cow in their backyard. Women for him are almost as elusive as dinosaurs. He sees them in movies but the actresses look nothing like the women he knew.

“mṛityuḥ sarva-haraśh chāham udbhavaśh cha bhaviṣhyatām

kīrtiḥ śhrīr vāk cha nārīṇāṁ smṛitir medhā dhṛitiḥ kṣhamā.”

The men at Mr Kabutar’s farm nod and yawn, as he reads out chapter 10, verse 34 from his leather-bound copy of the Bhagavad Gita. The old man wishes the men of his country would die too. Living in a world without any possibility of reproduction is the same as worrying about indigestion without consuming any food. Some men, the ones with generational wealth, fled to Azerbaijan and the Czech Republic to procreate with light-eyed women while others adopted children from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, but the men gathered here admonished such “unpatriotic” behavior. Two years ago, when the posh localities of Delhi, Bhopal and Mumbai were buzzing with blonde-haired children, running after their mothers who wore saris to appease their in-laws, the men of Gwalior had traveled to the Capital to take part in a silent protest at the Parliament House. Procuring children from poorer, more desperate countries isn’t a Herculean task but it is not in the spirit of nationalism. The old man worries for his grandson who hasn’t and may never, speak to a woman of his age. Mr. Kabutar’s voice streams into the old man’s ears.

“Shree Krishna is telling us of the qualities that make women glorious, fame, prosperity, perfect speech—”

Mr Agarwal interrupts him to say, “My astrologer has prophesied that the women will return on the first day of July.”

Mr Kabutar shuts his eyes in irritation but says nothing for this is part of Mr Agarwal’s routine. In a minute, he will look up at the baby blue sky and call out for his wife, “Sushma! Sushma!” The first time he did this, the men were shocked for it was well-known around town the beatings Mr Agarwal subjected his wife to. She had even filed an FIR against him a week before the women began to die. There were rumors around the country that the Nari-Mahamari was a natural consequence of the violence women have received at the hands of men. Countless convicted rapists, suspected flashers and husbands known for their bashings were burned on the streets in the hope it would convince the Goddesses of their goodness. The men had protected Mr Agarwal from being burned alive because he had borrowed money from them. As he begins to call out for his wife, the old man takes out a soggy biscuit from his front pocket and bites into it. Who would’ve thought men without women would appear more pitiful than women without men?

The old man sits on a mahogany chair, his partly bald head gleaming like a half-moon. His grandson stands by the grill window, peering out at the papery white bougainvillea swaying to a May breeze. At the age of nine, he was informed by his grandfather that women became flowers in their afterlife. Since then, he has spent countless hours admiring some of his favorite women—the yellow Amaltas, dangling like bracelets; the purple Jacaranda, too stubborn to drop down; the red Gulmohar, fleshy and fiery like the inside of a goat. How much longer must he go on like this? He is thinking of asking his father for money to study in Canada where he can meet a woman and bring her to Gwalior. Here, he will show her off to the old, debilitating men, and soon enough she will give birth to at least ten girls, blue-eyed and blonde-haired. They would start their mini-empire. He would wed each of his daughters to tall, broad-shouldered and wealthy men. He would be a patriarch, a monument of masculine ego. “Oye! Will you do me the honour of serving me dinner?” shouts the grandfather. The boy rushes to the kitchen and warms the leftovers from lunch. Potato and brinjal cooked in rapeseed oil with basmati rice. After placing the plate on the table before the slouching old man, he clicks play on the decades-old tape recorder and a voice, so thin it seems to slip across the marble floor and dash against the wall on the other end, streams out, filling the large hall. It’s the old man’s wife chanting the hymn, “Hare Krishna, Hare Rama,” recorded in July of 2004. The grandfather asks, “Will your father ever come out of his room?” The boy knocks at his father’s door.

“Papa, do you want to eat dinner?”

As usual, there is no answer. There seems to be no end to his prolonged hibernation. He had been a police officer, straight-faced and tight-lipped, who spoke to his wife twice each day, once in the morning to ask for a paratha and a cup of tea and once at night, to ask for rice and lentils. His wife had died in her sleep, turning blue and purple, as he slumbered at her side. The boy carries his grandfather’s dirty plate to the sink when suddenly, the bell rings and the men freeze where they are, their heads cocked to one side. The bell buzzes again. The old man tiptoes to the entrance, his eyes glued to the emerald green glass panels. He pulls the knob towards him and stands back, awaiting the heavy stride of a monster with black eyes. First enter the feet, then the legs, and in the end, the torso and head. The men begin to inch backwards as she walks towards them with long but light steps. Her round eyes seem to stare at nothing in particular and her gray lips are open as if in mid-sentence. She stops under the mustard bulb, the creases on her baby-pink salwar kameez resemble the scars of drought on a barren land. In the background, a dead woman chants.

The old man, his spindly fingers clutching his cotton shirt, blurts out, “Are you a woman?” The woman blinks anxiously and points to the soiled plate in the boy’s hand. For a moment, they stand still. The old man with a hand on his chest, the boy with his back against the sink and the Mona Lisa with an outstretched arm. The old man notices her arm, flush with long black hair. She must be the first of them, he decides. The women are finally returning. They have forgiven us. “Do you want food?” the old man asks. “Are you hungry?” She doesn’t answer but lets her outstretched arm oscillate at her side. He turns to his gaping grandson and orders him to bring over a fresh plate of leftovers. With a twitch in his left eye, he holds out a plate of potato and brinjal cooked in rapeseed oil. The grandfather ate the last of their basmati rice. The woman’s face is stoic like a hardened clump of papier-mâché. She looks nothing like the hip-thrusting women they see in movies. Her bosom is perfectly round and nearly touches her dimpled chin. It doesn’t matter whether she is beautiful or ugly. “Please take the plate,” the old man says sheepishly and clicks pause on the tape recorder. The boy parts his lips to let out a stream of gibberish. She takes the plate and slams it against the dining table, making the potatoes hop in the oil. She trails his face with the rough edges of her fingers. The grandfather stares from a distance, unable to control his joy. The woman’s stiff expression starts to loosen. Her darkly outlined features begin to melt and bob against her dotted skin. The sound of breathless laughter can be heard from behind the door and a moment later, the woman’s face breaks into a contorted mush of high-pitched laughter. Mr Kabutar bursts through the entrance with his rectangular body bent over and his head coming up for air every so often. The woman slips her hand inside her bra to retrieve two grapefruits. The woman, now a man, sits on the mahogany chair and undoes the pins that hold the hay-textured wig in place. Mr Kabutar stumbles past the boy and presents the grapefruits to the patriarch.

“You must try the Chakotra from my farm,” he says in between guffaws of laughter. “It’s rich in Vitamin C.”

The man sitting at the table massages his scalp. Reading his friend’s flummoxed expression, Mr Kabutar collects himself and explains, “Arey Bhaisaab, I am going around the colony distributing Chakotra as a gesture of goodwill. This boy—” he points to the boy dressed in a salwar kameez, “is my nephew. He is visiting from Canada.” The old man gestures to his grandson to take the grapefruits. At the door, Mr Kabutar turns to say, “Bhaisaab, the women will return soon but till then, we will make do with what we have.”

The boy’s father walks out of his bedroom with raised eyebrows and finds his son holding a grapefruit in either hand. He asks the patriarch, “Who was that?”

The old man says, “The last woman of Gwalior,” and clicks play on his tape recorder.

Thank you for reading paloma, a monthly art and literature magazine. For information on submitting your work, please see the Submission Guide. You can find us on Twitter and Instagram, and you can catch up on past issues here.

Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓

This was so good!! I can't believe I only just found this gem