Welcome to ISSUE 017: OULIPO ☁️

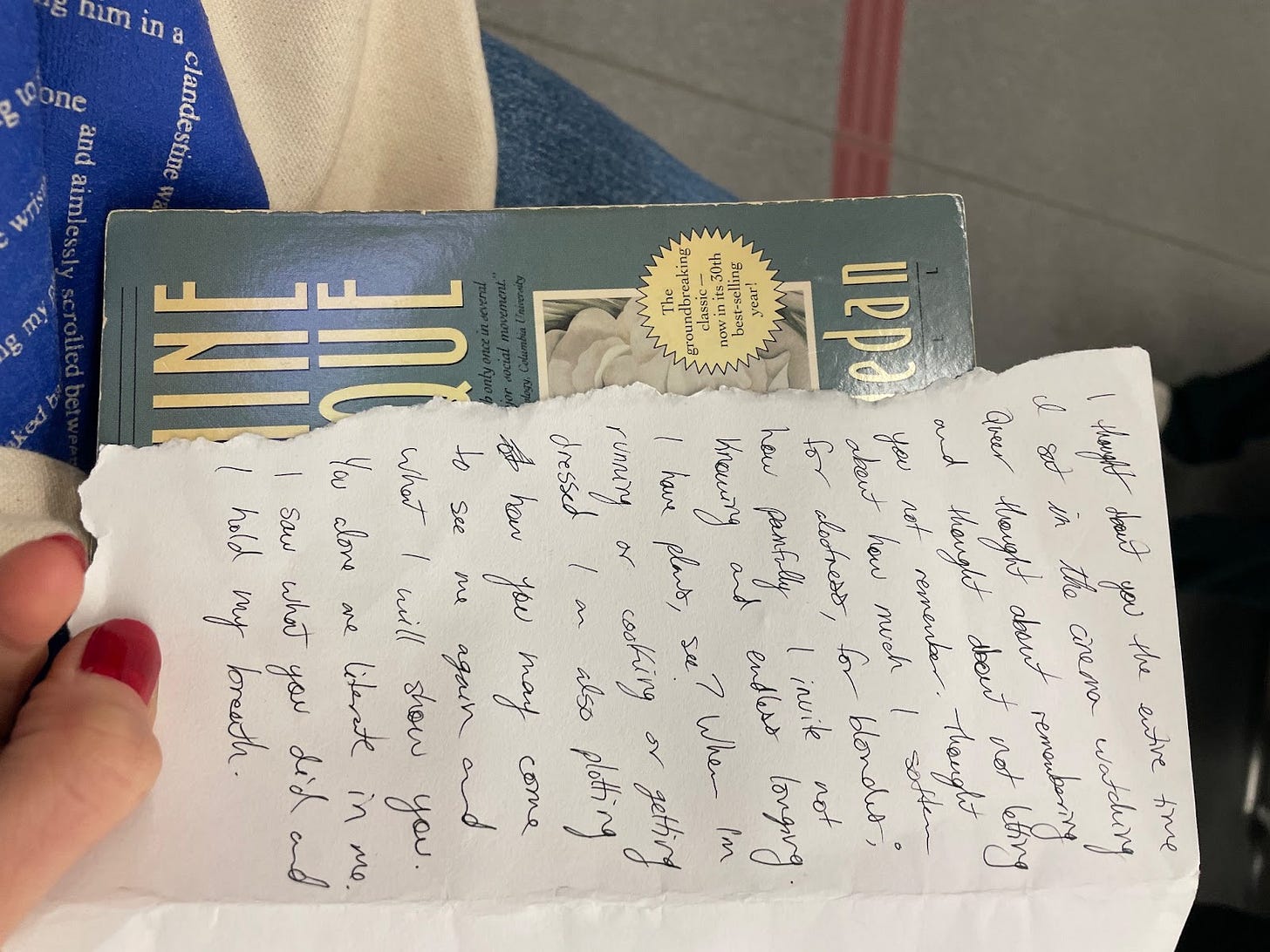

I went to see the new Luca Guadagnino film by myself the other week. Afterwards, I experienced clarity in somnambulism, a burning in my chest and a heat in my mind that told me live, you’re living, so come alive. It wasn’t that the movie was so great that it woke me up—the film is surreal, evenly-paced, dark (in content), and bright (in form), though not quite toothsome. But sometimes I become the right combination of inspired, lethargic, and bored such that my psyche takes what’s in front of it and entertains itself. As Daniel Craig and Drew Starkey’s perfect bodies danced around and beat into each other imperfectly, I thought about sex, about male validation, about birth, about addiction (to persons and substances and feelings), about rolling cigarettes. When I walked out of the cinema, I visualized pulling my ribcage apart like French doors so that I could swing open my own self. Everything external to me could come in and poke around at my insides and everything contained herein could dribble out onto the pavement. You’re living—touching, touched, losing, gaining. [My sober rendition of the movie’s Ayahuasca trip?] And then on the subway, I jotted down these thoughts on a scrap of paper:

“I thought about you the entire time I sat in the cinema watching Queer thought about remembering and thought about not letting you not remember. Thought about how much I soften for aloofness, for blondes; how painfully I invite not knowing and endless longing. I have plans, see? When I’m running or cooking or getting dressed I am also plotting how you may come to see me again and what I will show you. You alone are literate in me. I saw what you did and I hold my breath.”

In the movie, Lee (Craig) affirms his quest to talk without speaking, to be understood, recognized by an Other without the failures of language. In Allerton (Starkey), Lee finds a younger, less-definite-but-more-polished version of himself. The mirror through which he can finally reconcile his desire, his shame. I read Lee like this: If this self (Allerton) that is like him (but not him) can witness his self (Lee’s) without his having to fix or truncate his self in language, then maybe he can finally be. Be, without history, without context, without inhibition. Through this dance with an Other, Lee will choreograph his own coming-into self. Everything is cathected into Allerton, being known by him. But, of course, Lee’s love object is distant, unattainable—probably by design—and there is no real catharsis, only queer longing.

That’s what we’re doing here. Opening up, spilling out, sucking in through body and performance and, finally/fatally, language, in hopes that it will support some kind of confirmation (or exorcism). “A wordless union,” as Maya Parmenter puts it. In Jasmin Leigh’s words, “I long to touch despite the distance meter.” Lee (and Allerton) need this closeness, but it’s obstructed (by [internalized] homophobia, by addiction, by grief) by a (social, psychic, affective) blockade insurmountable by language. They therefore think, and move, and feel to make real, unreal, surreal their selves and their relation. It makes total sense, then, that after the credits rolled I thought about pulling myself apart and then I wrote about you—the movie made me want to matter and I need you for that.

This issue is poetic and poetry heavy, teasing the limits of communication and language and toying with themes of (re and mis) connection, shame, and longing. Annie Kemper’s non-fiction piece “No Shoes in Roma” tells us how important it is to do absolutely nothing—to connect with yourself, gently, seemingly passively, by way of others, being smart enough to let them happen to and around you while never granting the upper hand. In “Mirrors” and “A Sweet Euthanasiac,” Maya Parmenter reflects on how we bounce into and out of others, thinking about divine patterns, mundane inheritance, and sedative ephemera. “How does it sink? / Right in the ink,” writes Kyra MacFarlane in her playful and mysterious short poem, “It Melts.” What does it do, to sink (one’s teeth, an anchor, a body) and how is it done with words, in language? The material self, its limits and capacities, are considered at length in Jasmin Leigh’s “Body” while “Oulipo,” the poem we’ve echoed in the title of this issue, figures crowds, movement, and the construction of a world, of togetherness. Finally, Sara Javed Rathore’s short fiction “Pidar” recounts the tense longing between a daughter, her father and, adjacently, her mother. In this slippery triangulation of Self, Other, and the unspoken or unspeakable, all are “doomed to live with ghosts.”

| editor-in-chief

No Shoes in Roma by Annie Kemper [NON-FICTION]

Mirrors and A Sweet Euthanasiac by Maya Parmenter [POETRY]

It Melts by Kyra MacFarlane [POETRY]

Body and Oulipo by Jasmin Leigh [POETRY]

Pidar by Sara Javed Rathore [FICTION]

No Shoes in Roma by Annie Kemper | Instagram | Substack

You sit outside a café in Trastevere and your pale, American-sized legs won’t fit under the European-sized table so you cross them away to the side, invading the invisible border of another table’s space, too content to care.

You watch the tourists walk, their heads spinning on a swivel, craning their necks one way, then the other. The Italians walk with purpose, gazes straight ahead, cigarettes dangling from their mouths or held erect between their fingers.

You light a cigarette you won’t finish. This is what you’ve been doing for four days: sitting at cafés, sitting at restaurants, sitting on buses and thickly cushioned electric bike seats. Just looking. Sipping table red wine, table white wine, €17 cocktails, and watered-down Aperol spritzes you secretly love. You pound whole-milk cappuccinos twice a day and have never felt better.

You bite into everything: flaky bread, impossibly thin pizzas with fresh mushrooms and salami, bright and eggy carbonara, Roman-style oxtail resting in thick, dark tomato sauce. You bite into the creamy, swirled tops of gelato cones because you’re too impatient to lick.

You wrap yourself in heated towels post-shower, straight back to the bed to lounge, eating apricots, the juices trickling down your hands and staining the bedsheets. This is how you prefer to travel. You love doing this type of “nothing.” You crave it.

The two Danish businessmen next to you strike up a conversation. They vape with their sleek contraptions and wear some sort of hybrid athleisure pants that will never wrinkle. Their leather weekender bags are perched on their own seats.

One disappears inside and returns with another round of beers. You place your palm against your chest in gratitude. You’re oddly touched by this action. You don’t remember the last time someone wordlessly decided to buy you a drink. You’re closer to thirty than twenty, so you find this act “gentlemanly” as opposed to “presumptuous” or “predatory.”

You play out an entire scenario in your head in all of two seconds. Perhaps these two men will become your patrons for the rest of your trip. You’ll tag along to their dinners, their wine tastings, their last-minute private Colosseum tour that takes place at sunset, arranged by a friend of a friend. You’ll watch them consume dark liquor and beer all night and then slip away after they’ve passed out in their respective hotel rooms, mouths agape, snoring, their synthetic pants still on. (And wrinkle-free!)

Just then, you’re informed they leave for Florence. Tonight. Their lovely leather-trimmed weekender bags glare at you and tell you to fuck off.

The one with thick, veiny arms reveals his wife of sixteen years had an affair. Now, you understand your role. You listen.

“She was 23 when we got married,” he sighs, shrugging his shoulders, as if that fact is the main reason he finds himself in this predicament. You give him a coo of feigned sympathy. The veiny man sighs.

“I just feel very vulnerable right now, Annie.” He keeps saying your name after each thought.

“I just don’t know, Annie.”

“And, here’s the thing, Annie.”

“Listen, Annie.”

I’m a good man because I remember your name, Annie. My wife cheated on me, and it was completely one-sided and you must believe me, Annie. I am able to remember this detail I learned eleven minutes ago, and I need you to know and acknowledge that, Annie.

You’re having fun and want another beer, so you ask him if he’s getting a divorce.

You’re standing in the doorway of your Airbnb in the dark, barefoot. You walk down the cold marble stairs, across a sleeping courtyard, towards the entrance gate. There stands a handsome, actually sort of beautiful, Greek man. You FaceTimed him for about four minutes two hours ago.

He’s tall and slender with long eyelashes women pay hundreds of dollars to have permanently glued to their faces. You assumed, from his pictures, that his dark hair was speckled with sun-streaked blonde. You see now it’s actually salt-and-pepper gray, a bizarre contrast to his boyish face.

He watches you through the iron gates, smiling as you work your way through a stranger’s medieval iron key ring, trying to find the right one to let him in. He finally notices your feet and laughs all the way up to your apartment, trailing behind you, fingers grazing your back, shaking his head and repeating,

“No shoes in Roma!”

He rolls a cigarette, sitting on the bed, his head resting against the wall. You think about Airbnb fees. It’s too late. You ask him to roll one for you, too.

After minutes of profoundly honest chatter, the kind only strangers are able to share, he tells you he’s a “hedonist.” You raise an eyebrow but say nothing, mostly because you’re not actually sure what that means. Later, when you’re alone, you Google it and snort in laughter. Everyone’s a fucking hedonist. What an incredible line.

This hedonist is studying for his master’s in neuroscience. This hedonist’s parents are both dentists in Athens, Greece.

You ask what his plans are.

He glides his tongue over his rolling paper.

“I’ll get my PhD, of course.”

“Of course. And then, what?”

He shrugs, one of his tan freckled shoulders peeking out of his T-shirt, surveying the scene.

“God, I wish I lived in Europe,” you say.

He’s in no rush to go anywhere. To do anything. He likes chatting. He sips his wine and looks at you. He smokes his cigarettes and looks at you. You rise and grab your boring filtered cigarettes from the kitchen when you realize you might vomit if you consume another rolled one. It’s a game. Who acts first?

You drape yourself across the foot of the bed, set your wine glass on the floor, and prop yourself up on your elbows. Your black cotton dress has ridden up, now sitting too high on your thighs.You pull it back down.

“Now, why would you do that?” he mumbles as he leans over and meticulously adjusts the fabric back to the way he wants. You won.

“So, tell me everything you’ve done in Roma.”

“Nothing, really. Just how I like it.”

Mirrors by Maya Parmenter | Instagram

Tell me god, when you force two mirrors against each other which will be the first to Crack, shatter and split. My mother fed me frozen food To cope with my overleaping personality She hoped that the bland nature would Drown the embers she left. I will sit in your hall And sing the hymns of glory The cacophony of cherubs Implores me to believe. I will not. Tell me mother Am I nothing but an echo Of the dulcet lullabies That you sung in adoration For a child that would be nothing like you. I dowse myself in god’s dams daily I tell myself that i am dirty in need of cleansing But this doesn’t stop me From shedding my scaly skin. My inheritance.

A Sweet Euthanasiac by Maya Parmenter

I live for the sun dappled cobbles of the paths man made. The strips of indigo that gut the stars, in their remorseless embrace. My feet ache for the fronds that bend in sickly anticipation, a wordless union. My peels do not deceive them, nor the bluebottle who hovers: its charming wings marking my loss of a life never lived. Only witnessed by the orchids, that forgive and forget; with the same transience of what I long for.

It Melts by Kyra MacFarlane | Medium

Resilient in handcuffs Limbs and the limp I’ve dipped my cone In the bitter slime of nuclear waste Bliss in the periphery Sending an absurd asshole in limbo Oxbow How does it sink? Right in the ink

Body and Oulipo by Jasmin Leigh | Substack

Pidar by Sara Javed Rathore | Substack | Twitter | Instagram

I was twenty-one at that time—it was a strange time for me, as it is for many. One heartbreak, one degree, one year into therapy, one year with locks and kundis on my door so no one could barge in, one year since I reconnected with my father.

So, there we sat, father and I on two garden chairs; the staple of every Pakistani household, white and barred. Those garden chairs reminded him of kinnows peeled in Lahore’s winter sun, the sunlight that kissed his eyelids and knitted sweaters engulfing his form, or flames– smoke from the mouth as he stubbed out his last cigarette for the night on the delicate metal bars and pushed it back with the kreeench to get back up. That sound. Always reminiscent of the chair protesting, holding him back. “Don’t go,” it would say, “not right now, there are so many conversations to have, so many mugs of tea, so many cigarettes for the night.” My back would always hurt, even at twenty-one, after getting up from that white garden chair. A throne muddied by memories.

I had just had an argument with my mother–a screaming match.

“You’re ungrateful! An ungrateful wretch of a girl.”

“I am your daughter!”

I did not understand my mother—and she did not understand the woman I had become. It was worse when I was fifteen, or sixteen. We would scream and shout. I would rip my hair out. There are many things she had taught me to do during an argument: to lash out, to be angry like a mad dog, like a bad dog, to rush out and gnash my teeth and kill anything that came in front of me. I loved my mother, but I was too much like her. It scared me how much I was like her. But this is a story about a father and daughter. There have been many stories about mothers and daughters—and none of them are like ours.

My father, always the sinner, had listened from the stairs. I met him while scrambling up to my room and he gave my back two sharp raps on the shoulder, disapproving the screaming tone I had used with my mother.

“I’ll bring you chai.” I nodded. He couldn't do too much—my mother hated him. My mother hated me because I had his eyes, his lower jaw, his visage. She saw the man she hated in front of her every day, even in his absence. How could she not love him and hate him (me)? We were both doomed to live with ghosts.

I was still in my room, sitting in front of the heater when he stepped in with the chai.

“You’re not sleeping in the guest room?” my father curled an eyebrow up at me.

“No,” I said, “that’s where you sleep.” We would barely talk unless he was in the city, and he was barely in the city.

“Come, let’s talk and have chai on the roof,” I blurted out. I got up, fast, almost dropping my mug in the haste to connect to him in any way possible.

He nodded. “You’re not going to smoke your cigarettes?” he said, the disappointment tinging his voice lightly—he knew I smoked. He sat with me some nights and shared one. He still hated it. My mother said my father could quit anything—cigarettes (he did), her (he did), her (his shiny, new wife). But the never you was silent. When I didn't talk to him for a year my father came home and cried. This titan of a man, holding my hand and crying. This titan of a man I, for a time, hated. “Why don’t you love me? Do you know how much I love you?” I had turned my face away till he had gotten up from the foot of my bed and left.

Now, two years later, I was a little too eager. My father and I sat there on the garden chairs, chai in hand (sans cigarette—I quit two weeks after). “I think ammi doesn't love me,” I blurted out.

“She does. She is sick, you know she is sick. Don’t say that,” he said with a frown.

“She hates me.”

“Never say that to her.”

“She hates me because I look like you.” He laughed at that, raucously.

“You’re going to catch a cold. Your muscles will freeze up,” he replied.

“I love you, and I miss you so much,” I said, my voice trembling.

“You can always call me. You never do. You talk to your friends all the time on that phone.”

“I don’t know. I don’t know you.”

“Yes. It’s OK. You can start now.”

I took a long sigh and looked at my father’s skin aglow. Saturnine face shining in the moonlit night. I felt an overwhelming need to hold his hand and start sobbing, or hug him and tell him all that had happened to me. So much had happened to me, but here was this man with watchful eyes looking at the sky, and I knew too much of him and too little.

A friend recently asked me about my father’s hometown.

“How do you not know about Multan?” he gestured, eager and excited. “You have to ask him about the legend of Hari Singh Nalwa.” How would I tell him I barely knew my father? It made bile rise to my throat.

I went to his village once, to vote. A little girl approached me and asked me if I was a movie star—I was wearing a giant fur coat. “I know you,” she said eagerly, jumping up and down, “you star in that television drama.” I wanted to smile and brush it off, but my head gestured yes, and I thought I am a starlet and I am playing out my own downfall. I laughed. My father patted her head affectionately as she ran off barefoot in the street. She was playing with a boy that, my father told me, had cancer. He was lugging around a giant wheel, taken from the workshop nearby, and kicking it around with a long cane. This boy with cancer, no hair on his head, kicking around a wheel with a little girl who thought I was a city movie star. I thought of it as I saw my father walk down the road, past the mustard fields, hand in hand with his childhood friend. I didn’t know that, in the country, away from cities, men could hold each other’s hands without feeling an iota of shame.

“I want to know you. I want to,” I said now, turning to look at him fully and he pulled his shawl a little tighter.

“Go on. Ask,” his eyes were incredulous.

“I…don’t know what to ask. Where to start?”

He let out a chilly laugh. “How would you know when you have never done it? Talked to me?”

I let my breath come out in a silent scream of air and frost as he looked at the moonlit sky, and I looked at him. “OK.” He patted my shoulder then.

“I love you, and it's cold, you should wear a sweater. Take your medicines and get to bed. And, listen, don’t get angry at what your mother says. She loves you. She just doesn’t love me.”

And with a kreeench we got up from the garden chairs, as he walked me to my bedroom and then shut the door. “I love you,” he said before shutting the door, before I could reply. “I love you too, baba,” I whispered. Unheard.

Thank you for reading paloma, a monthly art and literature magazine. For information on submitting your work, please see the Submission Guide. You can find us on Twitter and Instagram, and you can catch up on past issues here.

Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓