Welcome to ISSUE 021: DARK LIGHT OF DAY 🫐

This morning I woke up with a headache burning behind my eyes. I think it is spiritual, this horrible, heavy ache. I’m carrying something with me, within me. The air is hot and dry and the sun is bigger than it ever has been before. It’s summer here, and summer always comes with a sense of foreboding. I go for a walk and my field of vision is like two tunnels of darkness laid out in front of me. The aura accompanying this migraine is an allegory of what is to come. There’s a deep pit of blue inside the summer, surrounded by the yellows and greens and pinks of the fields, the beaches, the skies. It’s like a promise, come close enough and you can see what I’m hiding inside myself. Something darker, grittier, just come closer, maybe you have it too.

I’ve been reading, because what else is there to do when you are hopeless? Maggie Nelson writes of the deep blue core within her in Bluets, explaining,

“I have spent a lot of time staring at this core in my own ‘dark chamber,’ and I can testify that it provides an excellent example of how blue gives way to darkness–and then how, without warning, the darkness grows up into a cone of light.”

I’m still in the dark light of day, waiting for my cone of light. I think I’ll look for it within these words, which become something brighter than words when they live in your head for a few days more. In Bluets, Nelson looks directly into the sun, “noticing the dark spot that flowers at its center,” and I think this dark spot makes everything beyond it all the more bright. Isn’t that what we are doing here? If we look into the darkness long enough, the rest of it explodes with light.

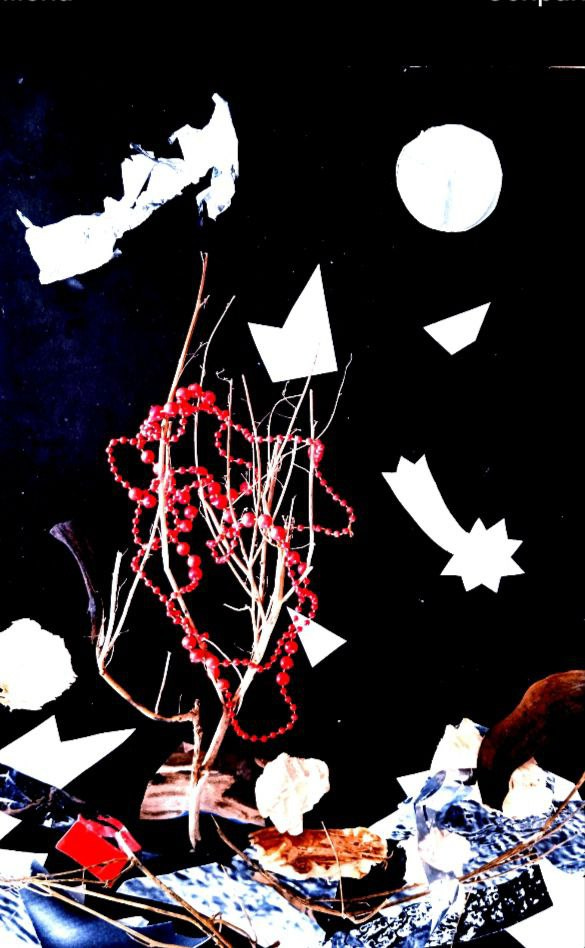

In this issue of , the light of our words erupts out of the darkness. Resident poetry editor writes of Soviet cinema, exploring the form and function of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1962 film, Ivan’s Childhood. Brittany Redd speaks to the void and the isolating nature of hunger in prose poetry that warns, “they can smell it on you, the emptiness.” Nasta Martyn’s visual art guides us through our uncertainty, with hues of crimson and cobalt, while ’s newest short story sheds light on the dark side of truth and its hidden consequences. Finally, poet Ali recalls Icarus in the “frenzy of the soar,” as he writes of aimless futility and intoxicating summer days.

So shield your eyes, take aim, and join us as we jump headfirst into ISSUE 021: DARK LIGHT OF DAY 🫐

| co-editor

Call for Submissions

PS. paloma magazine is currently inviting works of art, criticism, poetry, and prose that relates specifically to sexuality, eros, celibacy, self-actualization, and feminism, broadly conceived. The deadline for submissions to this special issue is Sunday, May 18. Learn more here (CLOSED).

Why Ivan’s Childhood is a Poem by Nilay Conraud [Culture]

Voidwalker by Brittany Redd [Prose Poetry]

Visual Art by Nasta Martyn [Visual Art]

Feminists Die a Sad Death by Vasundhara Singh [Fiction]

Against Platonic Love by Furqan Ali [Poetry]

Why Ivan’s Childhood is a Poem by Nilay Conraud | Substack

Andrei Tarkovsky’s cinema has often been described with the lingo of poetry; poetry, too, could benefit from having a different medium’s parameters applied to its conception. In 1962, Ivan’s Childhood marked the debut of Tarkovsky’s career, instantly earning him praise and recognition for ushering in a newly poetic approach to filmmaking. An approach nestled between reality and dream, borrowing from surrealist tropes and symbolic language, but void of irony—instead, concretely rooted in the human experience. It is the same, deliberate paradox of this rootedness I look for in a poem.

In opposition to Soviet cinema thus far, focused on action and formalism above all, Tarkovsky conquers the establishing shot as a dream wherein we find ourselves unable to run, or even move. He seeks not the actions but the space between them; not in awareness nor in dream, but in the middle, transcendent state of consciousness David Lynch calls “the white wall”. This is where Ivan exists, as demonstrated through the film's juxtapositions of his memories, nightmares, and vengeful waking state. As Ingmar Bergman famously said about Tarkovsky’s oeuvre, “When film is not a document, it is dream.”

Inevitably regrouped with other Soviet war films, such as Ballad of a Soldier (1959) or Battleship Potemkin (1925), Ivan’s Childhood stands out by offering the novel and horrific perspective of a child having lost everything to war. Childhood, as the viscous material our subconscious best feeds on, also helps grant access to what lies beyond the rational. A process of which only snapshots remain. For it is there, at the border separating the sacred from the profane, the teacher from the disciple, or the aware from the subconscious, that the film as a poem emerges.

Among the most memorable scenes in Ivan’s Childhood is one of macabre landscape: Ivan and his superiors tread with stealth over a waterlogged swamp to retrieve the bodies of fallen Soviet soldiers. Whether a swamp, a well, or singular drops, water is a recurring element, and one whose density further informs our trance-like experience of the film. Ivan, the child psychopomp, swims across bodies of water where “a grown man might drown”, and his sheer presence there speaks to the sentiment of a plea for a mission not to return from. Sometimes, the warmest hug is the coldest, dampest film. Other times, it is the simple image of a truck overflowing with fruit that pierces our heart. Metaphor is linkage—it uncovers that which exists both in the outside world and within us.

A poem is a place, and a place exists, and is measured, by our perceptions. The same architectural, methodical questions apply to the poem and to the film: What do we see, or smell? How high are the ceilings, how dusty the air? Does sunlight flood, or do we have to seek it out, in specific corners, at specific times? Does it inspire slumber, conversation, erotic desire? Does it tuck us away from the world, or faintly hint to the neighbors around? To be both within reality and observing it from outside requires the intent to see, hear, touch, smell, and taste.

I approach Tarkovsky’s work like I approach any poem: with reverence. Language is a lost & found where someone left a part of themself for me to find. Long scarves of verses and mismatched gloves making rhymes, the sentimental value of which I can surmise, more than access, based on my own experiences. And he who disagreed with people calling his films puzzles would not have it any other way. A poem does not speak to the conceptual, rational mind. It reaches for the inner divine before it reaches for logic. A poem searches, but not for a solution. Were Don Quixote's adventures in vain, or were they all the more significant for having been a product of his imagination? The poet, the filmmaker, and the child all show me the way within.

Furious, insurgent, scarred;

we are Tarkovsky’s Ivan.

Our childhoods, successions of

searching days and

the quiet, black-and-white

aftermath

that sleepwalks

behind our eyes.

Voidwalker by Brittany Redd

I didn’t always realize that most people don’t live with a void inside of them, a big gaping hole — a mouth — that’s always hungry, never satisfied. It never stops consuming — it’s all-consuming — it consumes me. Not all of me; it needs at least some of me to be alive. I’m like an incubator. The mother of unborn dark matter that doesn’t matter. It does not matter to anyone else. People ask how I am; I’ve learned to avoid the question. I stick to the surface of things. I’ve learned all the tricks. Wear shades so your eyes don’t get too hungry. Practice the smile in the mirror before you leave the house. The light won’t always bend around me how I want it to, but I try it anyway. Do it more than once; it’ll take more than one take to get it right. Try not to frighten the animals when you step out in daylight, moonlight, street light, any kind of light. They can smell it on you, the emptiness. Walk like you have a purpose beyond sucking all the air from a room. Walk like you have any purpose at all. Taller. Good. Let your eyes rest on the horizon. Make like you need to get there before you can drop the charade. You can make it that far. Don’t look down.

Visual Art by Nasta Martyn | Instagram

Feminists Die a Sad Death by Vasundhara Singh | Substack

I remember the day I received a bloody finger in my mail. I could immediately make out it was a woman’s because it was in equal measure rough and smooth. I still don’t know who sent it even though I have shortlisted a few names. I know the reason for someone sending me a woman’s bloody finger. Last month, I spoke at a conference in Delhi University on the topic ‘Is alimony killing Indian men?’ I spoke of how alimony affects far fewer people while dowry has affected more than a million women in the past few decades and yet the former is talked about with more anger. I then played an advertisement from the nineteen-eighties that had been released by the government in order to persuade people not to burn their wives and daughters-in-law for dowry. In the advertisement, a plastic doll is burned while a man speaks about the evils of killing women for money. The fire starts at the doll’s thick fingers and travels up to her round face and ponytail. At this point, I paused the video and said, “do you know why they burned her fingers first? Because a woman who has been bought from her family to work as a maid in the house of her in-laws carries all her power in her fingers that she uses to pick kankar from unpolished rice.” Somebody in the crowd recorded a video and uploaded it on social media platforms. This is not the first time my words have enraged men. A few years ago, my poorly made dummies were burned on the street outside the college where I work as a professor because I spoke about abortion for unmarried women.

You must be thinking, what did she do with the finger? At first, I wanted to wrap it up in newspaper and throw it in the bin but then I decided against it. The finger looked as if it still carried the life of the woman it was once attached to and I decided to bury it under the pink oleander bush in my garden. The envelope it came in did not have a name or address written on it. Instead, it bore the initials L.M. I told my colleagues about the finger and the initials and a few suggested it could be the initials of a person, perhaps the one who dismembered the finger or the one whose finger was dismembered. At night I imagine a man, his face featureless, slicing a finger off a woman’s hand and the woman squirming and screaming in pain. Since I received the finger in my mail, I have religiously followed the local news to find out information of any murder or mutilation but there has been none. The most recent news is of a wife burning her husband in order to live with her lover. The usual shenanigans. Before this, the most gruesome warnings I had received were of rape. The kind that makes you worry about the grammar of our country’s men. Most of them misspelled the word ‘rape’ and almost all of them did not know how to use adjectives.

I am not worried for my safety. I know most people don’t possess the guts to actually rape or mutilate me. They can bark to satisfy that mushy part of their ego that the world tramples upon. I am, however, bitterly impressed by the person who sent the finger. It must have taken gumption and sadism to perform an act so morbid. I don’t know if the finger belongs to his wife or girlfriend. It could also be the finger of his on-and-off lover, somebody he can leave behind without much guilt. I stop my car at the red light and roll down my window to greet Pinki, the transgender beggar, who I have known for fifteen years. She asks me, “did you find out who sent you the finger?” I shrug my shoulders. “I don’t know anyone whose initials are L.M.” She nods sincerely. “Have you been watering the finger everyday?” “I have,” I reply, “but it hasn’t grown into a woman.” She giggles. I hand her a hundred Rupee note and a few cigarettes.

I park my car in between two Altos and head inside the onion domed complex where I swim on the weekends. The complex also has a basketball and badminton court but those are always occupied by teenage boys. During summers, the swimming pool is open for women in the evenings (they don’t allow women and men to swim at the same time). I go into the changing room and take off my silk kaftan. When I am taking a shower, I realize that the pool is nearly empty. Then I remember today is Karva Chauth, the day when married women fast for their husbands. My longtime partner is German and I like to think the magic of the fast only works on Indian-origin men.

There are only two other women in the pool. One of them does freestyle in the deep end while the chubbier one floats in the shallow end. I start from the shallow end. I began swimming in the last year of my PhD when my chiropractor suggested I start exercising to relieve my chronic back pain. I swim past the chubby woman to the other end of the pool and then back again. I make sure not to bump into the woman swimming in the deep end. I stop for a minute in the shallow end before swimming another lap. This time when I return to the starting point, I see the chubby woman wrapping a towel around her waist and walking to the changing room. I swim to the deep end. When I return to the shallow end, I am out of breath. I look across the pool and do not see the other woman. “You are famous,” a woman’s deep voice startles me. I turn to my side to see the woman in a pink swimming costume. She has a crooked smile and the bags under her eyes make her look older than she is.

“Yes?”

“You are famous,” the woman repeats, “I read your articles.”

“That’s great. I hope you like some of what I write.”

The woman laughs with her head tilted back. “I like almost all of it. You are brave.”

I shake my head in an attempt to appear modest. “Do you come here often?”

“Oh no. I don’t get the time. My daughter is in fourth standard. She has her dancing classes on the weekend.”

“Well, I think we should continue swimming before it gets late,” I say.

Just as I am about to immerse myself in the water, the woman says, “I am a writer too. Not as famous as you are but I am working on a novel. I have the first draft in my bag if you would like to check it out. I am sure you have connections in the publishing world.”

“Sure,” I say and go in for another lap.

In the changing room, I see the woman in the pink swimming costume change into an off-white kurta. When I am done drying my hair, I nod to the woman who gestures to me to wait. She takes out a spiral bound draft of her novel from her tote bag and offers it to me.

“If you get time, please read it.”

“I will,” I say, politely and begin walking out of the changing room.

“Oh!” The woman says, “I didn’t give you my number. How else will you tell me whether you liked my work or not.”

I walk back to the woman with a forced smile. I take out my cell phone and start dialing the digits she utters.

“Should I repeat it?”

“No, that is not necessary. Your name?”

“Lata Mishra. You can save it as L.M.”

I look at her grinning face and then at her hands. There is a finger missing on her left hand. I run out of the changing room and drive my car out of the complex. I do not look back.

When I reach my house, I phone my husband who is in Bhutan interviewing monks. He does not pick up. I pace the living room with hands on my hips, unable to erase the image of the woman’s grinning face. I open the draft of her novel which has nothing but blank pages. I return it to the dining table. Then I pick it up again and open the very last page. ‘Feminists die a sad death. Proceed with caution,’ is written in cursive.

At night, I go out to the garden and dig with my hands till I find the partly decomposed finger. I put it in a plastic bag and take it inside the house.

Against Platonic Love by Furqan Ali | Instagram | Substack

Sitting aimlessly on Eid day,

Thinking about the futility of the aeon,

I thought of the fractious spell

And the resultant intoxication I had, even

After years and years of encounter.

Peshawar is far more subliminal than Eden—

I can touch and lurch in the scent of the gated city

And prostrate upon it.

What maiden houris of the afterlife,

With a lightning appearance,

Pristine countenance,

And godly silhouette,

Could hold to the eyes of this crooked earthling

The wax of your ear,

The rusted steel nose pin,

Greyish, catastrophic hairs,

And the acned cheeks of yours?

Ah, the sensation of the earthly viscera,

The dysmorphia of every kind and sort—

It is incomparable to the untouchable,

and the non-sensorous holiest of holies.

Icarus vaporized in this

Frenzy of the soar—

And so too the frustrated ones,

Whose beloved is exalted,

And merely and pathetically exalted

Thank you for reading paloma, a monthly art and literature magazine. For information on submitting your work, please see the Submission Guide. You can find us on Twitter and Instagram, and you can catch up on past issues here.

Subscribe today to receive the next issue directly to your inbox ↓

Powerhouse issue 😤

Feminists Die a Sad Death by Vasundhara Singh

I haven't finished reading all the write up yet but this one is one of the best most captivating piece I have read in a while